A New Movie Takes On the Man Who Exposed Some of the Biggest Cover-Ups in US History

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">

(min-width: 1024px)709px,

(min-width: 768px)620px,

calc(100vw - 30px)" width="1560">“In case anyone cares,” the investigative reporter Seymour Hersh moans somewhere in the middle of Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’ documentary Cover-Up , “this is becoming less and less fun.”

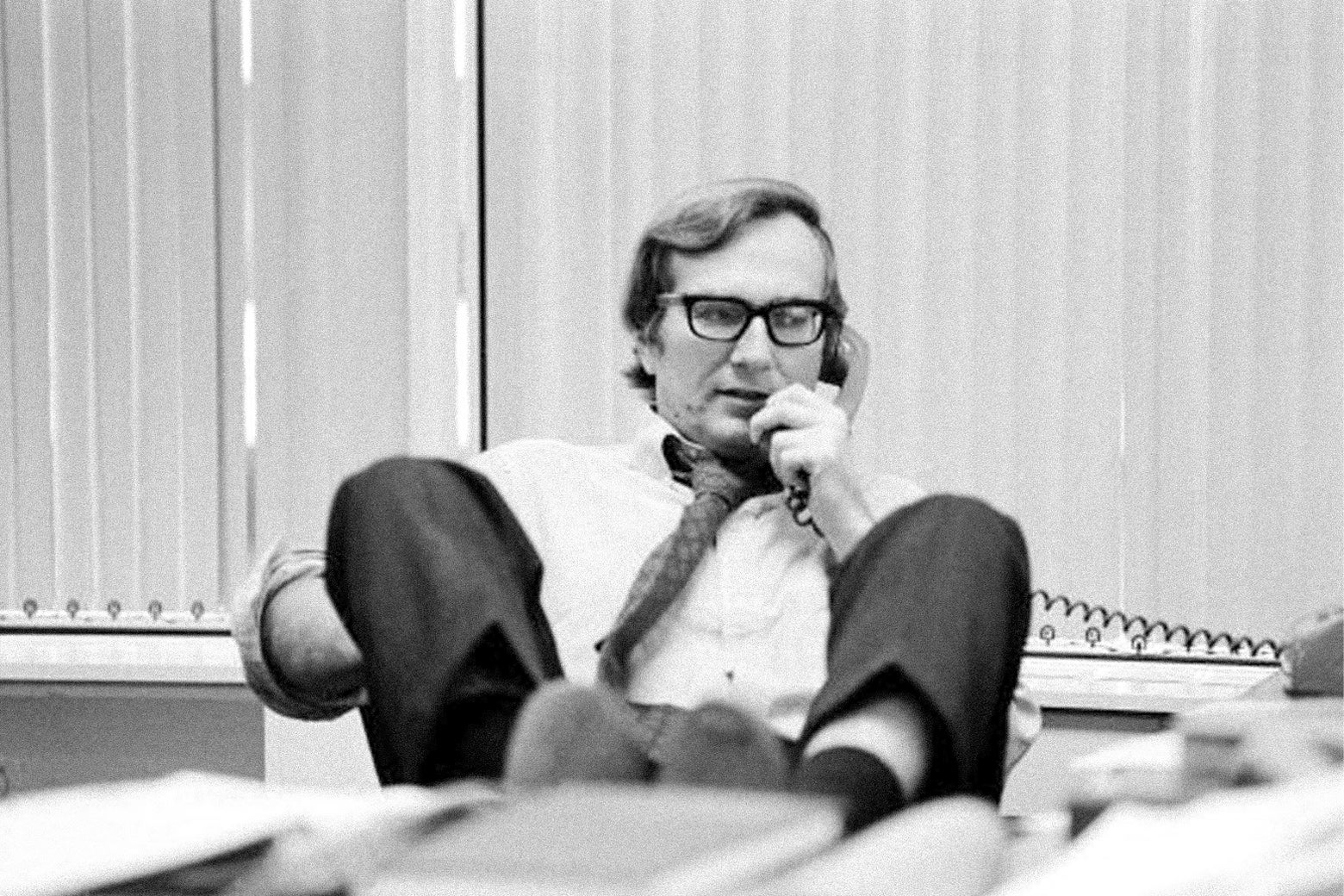

Hersh, who broke the stories of the My Lai massacre and (along with 60 Minutes II ) the torture at Abu Ghraib, is perhaps as close to a living legend as the last 50 years of American journalism has produced. If he's not a household name on the level of Woodward and Bernstein, with whom he traded scoops on the Watergate break-in, it might be because his career is too far-reaching to be reduced to a single story, or maybe it's just that he was never portrayed by Dustin Hoffman. But he's a tricky subject for a documentary, because, as Cover-Up establishes right at the outset, he's not crazy about being reported on himself.

Poitras, the director of the Peabody-winning All the Beauty and the Bloodshed and the Oscar-winning Citizenfour , spent 20 years trying to convince Hersh to sit in front of her camera, but not even teaming up with Obenhaus, Hersh's past collaborator on films for PBS's Frontline , could put their subject at ease. The pair seem to have planned a kind of procedural deep dive, not just recounting Hersh's many scoops but detailing how he got them. But while the film shows stacks of bankers boxes filled with documents relating to Hersh's articles, he rebels almost immediately at the thought of opening them up, lest he inadvertently exposes a past source. “This is all supposed to be after death,” he protests, and while he's talking about preserving his contacts' anonymity, it seems like he would also die sooner than risk exposing himself.

Poitras' films about Edward Snowden and Julian Assange are both procedurals and portraits, consumed by two questions: What does it take to break through the walls of secrecy erected around powerful institutions' misdeeds, and what kind of person is willing to do it? In Hersh's case, that means an abiding commitment to justice coupled with overwhelming determination and confidence to match. When, in 1972, he thought it was time for the New York Times to hire him, he sent editor AM Rosenthal a letter that began, “How about a job?” Without that self-assurance, Hersh might not have been able to persist in penetrating the layers of deceit and obfuscation that make great journalism such a difficulty and draining process. But it hasn't always stood him in good stead in recent decades. His alternate history of the killing of Osama bin Laden was widely criticized for relying largely on a single unnamed source, and allowed James Kirchick, writing in Slate in 2015, to dismiss him as a mother “ crank .”

In Cover-Up , Hersh readily admits that he's made errors, but his admission veers past frank to glib: “If I have ever made the claim to be perfect … I withdraw it.” At one point, he's questioned about a story based on information from a longtime source, and Hersh snaps back that if this new story is wrong, “I've been wrong for 20 years.” As he asks it, the question isn't soul-searching but rhetorical: Of course he hasn't been wrong. But then he is the person whom Richard Nixon is on tape describing as “a son of a bitch—but he's usually right, isn't he?”

Hersh describes himself as someone whose talent for instantly connecting with strangers was honest behind the counter of his family's dry-cleaning store when he was a teenager. But, like Snowden and Assange, he seems now like a person hardened by too many years of poking into the shadows, someone whose paranoid hunches were proved right too often for him to ever let down his guard. “It's complicated to know who to trust,” he tells the filmmakers, whom he has known for decades. “I mean, I barely trust you guys.”

At one point, in fact, Hersh very nearly leaves the film on-camera, after Poitras and Obenhaus push too hard about wanting to get a look at his notes. He's concerned about revealing the origins of his information, of course—what little look we do get at his battered yellow legal pads includes several sections that are blurred or blacked out (although, given how challenging it is to read what we are able to see, I'm not sure the camouflage was entirely necessary). But this opacity also serves to keep Hersh's work as a black box of his own, resting on a kind of bedrock faith in prestigious journalistic outlets—surely the Times or the New Yorker wouldn't publish it if it wasn't so—that can be scarce in the present era. That's not to say that Hersh falls back on institutional credibility: He all but says that the New York Times fired him when he proposed to turn the same investigative tools he had used on the federal government toward reporting on corporate interests. And he hardly has that to back him up anymore: Although Hersh's New Yorker bio still lists him as a “regular contributor,” he hasn't published in the magazine since 2015 and now does most of his writing on Substack. His oversight has diminished, along with his influence.

Hersh allows that his famous Abu Ghraib scoop might not even have been published if he hadn't had those indelible images of American soldiers torturing Iraqi prisoners to accompany it: “No photos, no story.” But it was Hersh's words, and his byline, that gave those images weight, connecting the abuses committed in one misbegotten war to one begun almost 40 years earlier. Follow Hersh's life and his work through the decades, as Cover-Up does, and the dwindling of his kind of no-words-minced reporting seems like a dark development indeed. Cover-Up introduces Hersh with a slowed-down shot from an old television interview, stretching out the moment so he seems to be gassing into the middle distance, as if he's shouldering the weight of all the world's evils. But on that same broadcast, he's asked about the denials of his My Lai story, and responds, without equivocation, that the Army is “lying through its teeth.” Imagine if mainstream reporters could still speak so plainly.