This App Warns You When ICE Is Nearby. It Might Not Be Enough.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

The Trump administration continues to detain, expel, and imprison thousands of Americans for the most cruel and arbitrary reasons, helped in no small part by the advanced surveillance networks provided by Silicon Valley contractors: sweeping databases of sensitive information, sophisticated tracking devices , facial recognition software, social media screening . In response, tech-savvy users are taking to social media platforms and encrypted messaging apps to warn their communities, in real time, of encroachments from immigration agents. Some are even going beyond that—by building their own tools to fight back.

At first, shortly after Donald Trump's inauguration, these efforts took a local, focused approach: community advocates in the Long Island town of Islip crafting a live map of verified Immigration and Customs Enforcement sightings in Suffolk County , and developer Joanna Benavidez setting up a limited-access app to track ICE appearances in the frequently raided immigrant town of El Cajon, California. From there, the website People Over Papers began tracking ICE arrests in Washington state, using a volunteer team of moderators to review anonymous reports. Its digital map, hosted on the virtual canvas platform Padlet, now takes a nationwide view. There's also ResistMap , a network from the Turn Left PAC that solicits ICE agent–sighting reports via a form, displays verified sightings on a map, and allows users to opt in for text alerts. As for smartphones, there's SignalSafe, a mapping app that collects anonymous, crowdsourced ICE agent alerts and accompanies them with submitted photos, videos, and text notes . The Mexican government has even launched an app, ConsulApp Contigo , that allows Mexican Americans to quickly notify their home country's consulate if they get in any trouble with ICE, then be connected to legal help or get a message out to their family and friends.

It's a heartening groundswell of effort, but these quickly assembled creations have their limits. It's understandable why the Suffolk County activists want to focus their time and bandwidth on their immediate and heavily policed surroundings; it's also understandable why the El Cajon developer isn't spilling much when it comes to her app's access and its name. For all these developers, the worry of bad actors weaponizing their apps, and of ICE agents potentially retaliating against their work, is potent.

Scaling to serve the entire country also makes these efforts all the more complex. Volunteer moderators may only have so much time on their hands, and only so much ability to verify a sighting that's been reported to them from a city that may be thousands of miles away from their remote location. And although an added layer of bureaucracy—whether via human screeners or a Google form—may help ensure the spread of trustworthy information, it also slows things down and hampers the urgency of the effort. For apps that work across various phones and platforms, there are all sorts of dangerous privacy intrusions; if your computer or smartphone sends its IP address, location data, photographs, or other user-identifying info to a program's centralized server, you can imagine that Homeland Security will take advantage of that. Just ask Google and Facebook .

That's why another platform, called ICEBlock , is hoping to bypass those issues through ample security and automation. Joshua Aaron, a longtime software engineer and former bassist for the famous Napster-era power-pop band the Rosenbergs , is single-handedly coding and funding the app, symbolized on Apple's App Store with an illustrated logo featuring a melting ice cube. It's an a program in many ways: It's available for download only on the iPhone, it does not require a formal account or cost any money, it purports to collect no user information, and it offers no typical pixelated ads.

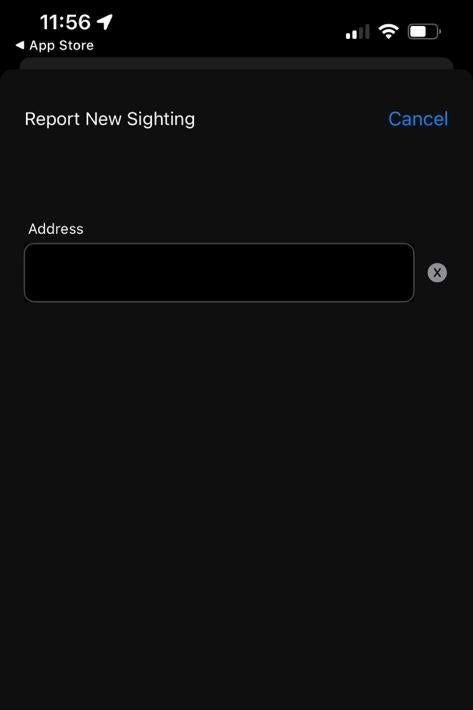

The basic thrust of the app lies in this limited functionality: With your iPhone's location turned on, you can easily report the sighting of any ICE officers you spot within a 5-mile vicinity; if other app users are located within that radius and have their notifications turned on, they'll receive a heads-up push about that spotting. (This is especially helpful in dense cities like New York.) There are no photo attachments or voice recordings involved here, and because the app offers no storage system, reported sightings disappear from ICEBlock after just four hours. To protect the system from abuse, users are not allowed to report sightings more than once every five minutes. The app is also available in 13 languages, including Arabic, Nepali, Spanish, and Vietnamese.

I first heard about ICEBlock through various posts by former Rosenbergs front man David Fagin, who has been raising awareness on behalf of his onetime bandmate. Though he's generally kept low-key about his efforts, Aaron agreed to chat with Slate since he stands by the legality of his app (“I consulted multiple attorneys, and the app does not encourage any illegal activities”) and has engaged in some linked promotions on social media, replying to high-profile accounts who share stories about ICE outrages.

“I haven't talked about it with anyone except for my wife and a few very close friends,” Aaron told me. “A few big accounts have reposted our links, though, which has helped get us a few hundred downloads.”

Events like the extrajudicial rendition of Kilmar Abrego Garcia also persuaded Aaron to bring more attention to ICEBlock. “I'm really concerned about the rights of individuals. I'm concerned about the erosion of our civil liberties, including the lack of due process,” he told me. “Sharing information about ICE activity, I think, can be crucial for certain communities.”

Aaron has a deep knowledge of software architecture: He created the web-hosting platform BootBox decades ago and went on to work for Apple in the early 2000s, going on to start his own tech-consulting firm, Mac Genius , after leaving the Big Tech giant. This experience is reflected in ICEBlock's sophisticated, simple architecture. Within the app, ICEBlock provides a detailed guide to the few buttons featured within, as well as the settings necessary for operation. It even includes a disclaimer against “interfering with law enforcement.” (It is not illegal to report on ICE agents who are generally walking around, but it is illegal to obstruct them in any way while they're in the middle of serving a warrant or searching a home.) In addition to receiving updates about ICE sightings, users can get a tracking of just how far they are, measured in miles, from a purported sighting. The wide language selection was inspired by research Aaron did on various immigrant communities, and ICEBlock appears in whatever default language a user's phone has. And, he insisted, “it stores no emails, device IDs, or IP addresses.”

Of course, this further limits the potential for ICEBlock's reach wider. The app is not available on the Google Play Store because its terms require that “the ID of every user be stored in a database that would make it possible for any government official to subpoena the developer for information,” Fagin wrote to me. (That certainly has happened before .) This also precludes ICEBlock's inclusion in any third-party stores. Those privacy boundaries perhaps speak more to the predatory nature of the tech companies that control the bulk of our infrastructure, from encrypted group chats to facial recognition. Apple just had to settle a class-action lawsuit over allegations that it used Siri to secretly record user conversations and transmit them to third parties. You might as well use your iPhone to access an app that could help other people, instead.

The addition of ICEBlock to the corpus of homegrown anti-detention apps is a welcome indicator that grassroots momentum for immigration advocacy hasn't let up. It's also a test, however, for the sustainability of the tech resistance under a far more aggressive and brazen Trump 2.0 regime. At least one such effort, the sighting map Juntos Seguros , has already shut down. The ability to reach the immigrants who most need such alerts is dependent on whether they can afford or use private American tech—and whether they even have phones that weren't originally provided by ICE itself in order to track them. And there will, inevitably, be attempts by ICE agents to work undercover and hijack these apps for their own uses; there's a reason they're already using face masks and plainclothes disguises to sidestep easy attention.

Should all these apps be adopted and used more widely, we'll likely get to find out the answer to another chilling question: whether there's any possible way for Americans to shield themselves from the Trump administration's wide-ranging dragnet . The stakes are existential.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.