The Rise and Fall of Chess Stars. Anniversaries

LaPresse

Chess approached philosophically

Fifty years ago, Bobby Fischer's brilliant career was coming to a close, while a new protagonist emerged within the Soviet ranks, poised for a decade of unchallenged dominance: Anatoly Karpov. Ten years later, he was powerless against the emergence of the greatest of all time: Garry Kasparov.

Fifty years ago, a wonderful American chess career came to an end, with the passing of the brightest star the game had ever known, Robert James Fischer . Also fifty years ago, a new, explosive protagonist began to emerge from the silent but crowded ranks of the Soviet Union: Anatoly Karpov .

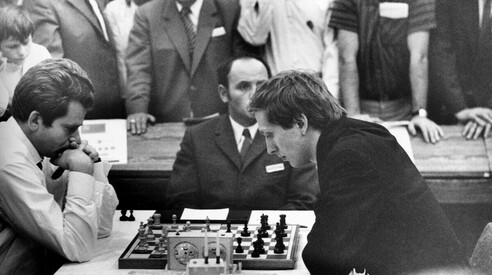

Nearly three years had passed since the celebrated match of the century between "Bobby" and the Russian Boris Spassky. The former had triumphed, violently snatching the world crown from the entire Soviet chess machine, which had held it for decades. He had done it alone, and he had done it with great fanfare. Chess was suddenly on the news, it was written about in the most diverse magazines, the rare photos of the American champion ended up on every cover . But Bobby, at the height of his success, disappeared . He didn't play a single tournament game, he didn't play (after exhausting and at times grotesque negotiations) the match to retain the title, which would have seen him face his challenger: Karpov, precisely.

Exactly fifty years ago, on August 20, 1975, Karpov made his first appearance as world champion, in Milan, Italy. His victory inaugurated a decade of unchallenged dominance . The responsibilities of a champion, it's easy to imagine, can be burdensome, oppressive, intolerable. And Karpov found this colossal burden on his shoulders without having had the chance to wrest it from the rival "Atlas," Fischer, who had lifted him so high, and then, like Sisyphus, had watched (or rather, made) him fall inexorably back to earth.

But Karpov had the makings of a true champion, a Hercules aware of his struggles, and equally conscious of his duty to face them. It was a duty to the party, which had supported him since he was a boy, to the country, for which he represented redemption, but also to chess itself. His (first) rival, fellow citizen and later deserter Victor Korchnoi, loved to remind Anatoly of his (supposed) inferiority to Fischer, or, rather, to the ghost of a player he once was. Karpov wasn't interested. He wasn't interested in being the face of magazine covers (nor was he particularly photogenic), he wasn't interested in being a burning flame that could be extinguished by the first gust of wind. He was interested in being a giant, in being a rock, in being a foundation. He was interested in teaching, and above all, he was interested in winning.

Forty years ago, a remarkable chess career came to an end. This time, it was Anatoly Karpov's. The Russian rock that had smothered the American flame was powerless against a supernova, a burst of energy that could only have come from the greatest of all time. His name? Garry Kasparov.

The match: Karpov vs. Unzicker, 1-0 A strategic question: What iconic move does White make in this position to secure control of the a-file?

More on these topics:

ilmanifesto