Poland's EU-funded foreigner integration centers have stirred controversy – and misinformation

By Małgorzata Tomczak

Petitions, referendums, protests, and vocal opposition from local and national politicians have thrust “foreigner integration centers” (Centra Integracji Cudzoziemców – CICs) into the heart of Poland's polarizing political debates in recent months.

The centers – whose objective is to support legally residing foreigners with services like Polish language courses, legal and psychological aid, vocational training, and cultural workshops – have been weaponized to boost public anxieties about migration and to attack the current government, especially in the context of the recent presidential election.

Amplified by right-wing rhetoric, the controversy around the centers has been driven by a wave of misinformation and misunderstanding about their purpose and operations, including false claims that they will be used to house illegal immigrants.

Małgorzata Tomczak, a journalist and PhD researcher specialized in migration, describes the extent of opposition to CICs and explains how they were conceived and what their purpose is.

The backlash against the centersThe discussion around CICs erupted in October 2024, after the ruling coalition unveiled its migration strategy for the years 2025-2030, part of which includes the creation of 49 CICs , whose creation is funded by the European Union.

The announcement sparked an immediate backlash, fueled by social media campaigns and comments from politicians, particularly from the two main opposition parties, the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) and the far-right Confederation. Critics falsely linked CICs with the EU's migration pact, claiming that their objective is to facilitate the relocation of irregular migrants to Poland.

PiS spokesman Rafał Bochenek, for example, wrote that “they want to launch the Foreigner Integration Centers in Poland in connection – de facto – with the implementation of the migration pact and the relocation of migrants to Poland.”

Yesterday's announcement by Tusk regarding the migration strategy is just a smokescreen and a distraction from the policy they are actually pursuing... the best proof of this are the Foreigner Integration Centers they want to launch in Poland in connection with - de facto - the implementation of the pact...

— Rafal Bochenek (@RafalBochenek) October 13, 2024

In the following months, numerous demonstrations took place in municipalities where centers were planned to be opened.

In December 2024, a banner stating “No to foreigner centers in Płock” was unfurled across a walkway in the city of Płock, with Marek Tucholski, co-chairman of Confederation's local branch, sharing his approval of the message on social media.

In April 2025, PiS organized a demonstration against the centers in Płock, attended by party MPs Wioletta Kulpa and Janusz Kowalski as well as far-right activist and former PiS election candidate Robert Bąkiewicz.

In Siedlce, a group led by Bąkiewicz, “Roty Marchszu Niepodległości”, drove a trailer with anti-CIC slogans through the city. Confederation MP Krzysztof Mulawa promoted a petition under the slogan “Stop immigrants in Siedlce”, which framed the centers as a threat to national security and identity.

In March 2025, Radom city council meetings were disrupted by residents supported by right-wing activists, who demanded the immediate halt of CIC plans. Meanwhile, the head of the local assembly in Małopolska province, PiS's Łukasz Smółka, declared in April 2025 that the region would resist joining the network of centers.

A province in Poland has announced that it will not participate in government plans to establish EU-funded integration centers for immigrants.

Protests against the centers, 49 of which are planned to be set up in Poland, have taken place in various cities https://t.co/BqqM8PG6p5

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) April 18, 2025

Similar campaigns occurred in the cities of Suwałki, Żyrardów and Częstochowa, where residents signed petitions against CICs, citing safety concerns and a lack of transparency in informing locals about the facilities.

In Legnica, a protest was held outside city hall, with demonstrators, joined by Bąkiewicz, chanting “No to illegal migrants” and warning of “culturally alien” arrivals.

In Piotrków Trybunalski, protesters – including local residents, PiS councilors and Bąkiewicz with its newly formed “Border Defense Movement” – disrupted two council sessions, presenting a petition against the creation of a center in the city.

PO councilors in Piotrków Trybunalski chickened out and didn't come to the session on the Foreigners' Integration Center. Thus, the blackmail of the PO Marshal was effective: either you build the center, or we take your money for projects. An unbelievable scandal. pic.twitter.com/waR1W7AMxJ

— Krzysztof Ciecióra (@k_cieciora) April 25, 2025

The aforementioned protests and campaigns varied in scope, with around 500 people demonstrating in Płock and Piotrków Trybunalski, and about 200 in Włocławek. About 2,300 people signed the petition in Legnica, with more than 7,100 signatures in Siedlce and more than 4,600 in Radom.

Most of the protests and campaigns shared some common features.

First, they were usually organized by PiS, Confederation or far-right groups, who framed CICs as part of an EU plot to force illegal migration upon Poland. Capitalizing on anti-EU sentiment and broader fears around migration , conservative and radical right politicians and activists portrayed the centers as evidence of the alleged out-of-control, pro-migration policies of the government.

A large majority of Poles support reintroducing border controls within the EU to curb migration, a poll has found.

If introduced long term, such a measure would effectively end the Schengen Area that allows travel across most of Europe without checks https://t.co/55mqLNL3mZ

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) February 3, 2025

Second, although the protests and petitions were often organized and led by figures from political parties and groups, their initiators frequently claimed to be acting on behalf of local residents, thus suggesting there was grassroots support for actions against CICs.

Finally, the protests focused on fears around safety and cultural disruption as well as the lack of consultation with local citizens, while spreading misinformation about the actual objectives, scope and origin of CICs.

What are the centres?In actual fact, and as members of the current ruling coalition regularly point out, CICs were first conceived under the former PiS government in 2017 as part of the pilot project “Building Structures for Immigrant Integration”, funded by the EU's Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund (AMIF).

Launched in 2021 – when PiS was still in power – with the opening of two centers in the Opole and Wielkopolska provinces, the initiative expanded after the outbreak of full-scale war in Ukraine. By the end of 2023, there were six centers operating (five in Wielkopolska province and one in Opole).

Currently, 20 CICs are in operation – four in Lublin province, four in Małopolska, four in Wielkopolska and two in Lower Silesia, as well as four in the city of Łódź, one in Zielona Góra and one in Rzeszów.

By the end of 2025, the government is aiming to operate 49 CICs in total, with at least one operating in each of the larger cities in Poland.

Poland is establishing 49 "foreigner integration centers" to help coordinate services for the country's growing number of immigrants.

The EU-funded facilities will provide courses in the Polish language and adaptation as well as offering legal advice https://t.co/unuT7f5Bvv

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 11, 2024

The purpose of the centers is to support the social, legal, cultural and economic integration of foreigners legally residing in Poland. They operate as “one-stop shops”, offering multiple types of assistance in one location to minimize bureaucratic complexity.

All services offered by CICs are free of charge and typically include activities such as legal and administrative assistance (help with residence or work permits, assistance with navigating social security or tax matters and when contacting schools, hospitals etc.), language courses, job search support, psychological support, assistance with translation of documents, as well as involvement in cultural and social activities.

For example, one of the CICs in Łódź offers translation services in six languages, a specialized Polish language course tailored to academic and professional needs, as well as workshops on consumer rights, taxation rules and setting up a business in Poland.

That center also hosts educational and networking sessions about current job market trends in Łódź as well as recreational and integration activities, such as outdoor picnics and a workshop called “Polish Countryside Traditions”, which introduces participants to Poland's rural customs.

Importantly, CICs only offer services that support integration – they do not provide financial assistance or housing.

Contrary to the claims persistently repeated by nationalists – such as President-elect Karol Nawrocki, who during an election debate on 23 May called them “apartments for illegal migrants” – and the far right, their services can be used only by foreigners who already legally reside in Poland, not irregular migrants or asylum seekers.

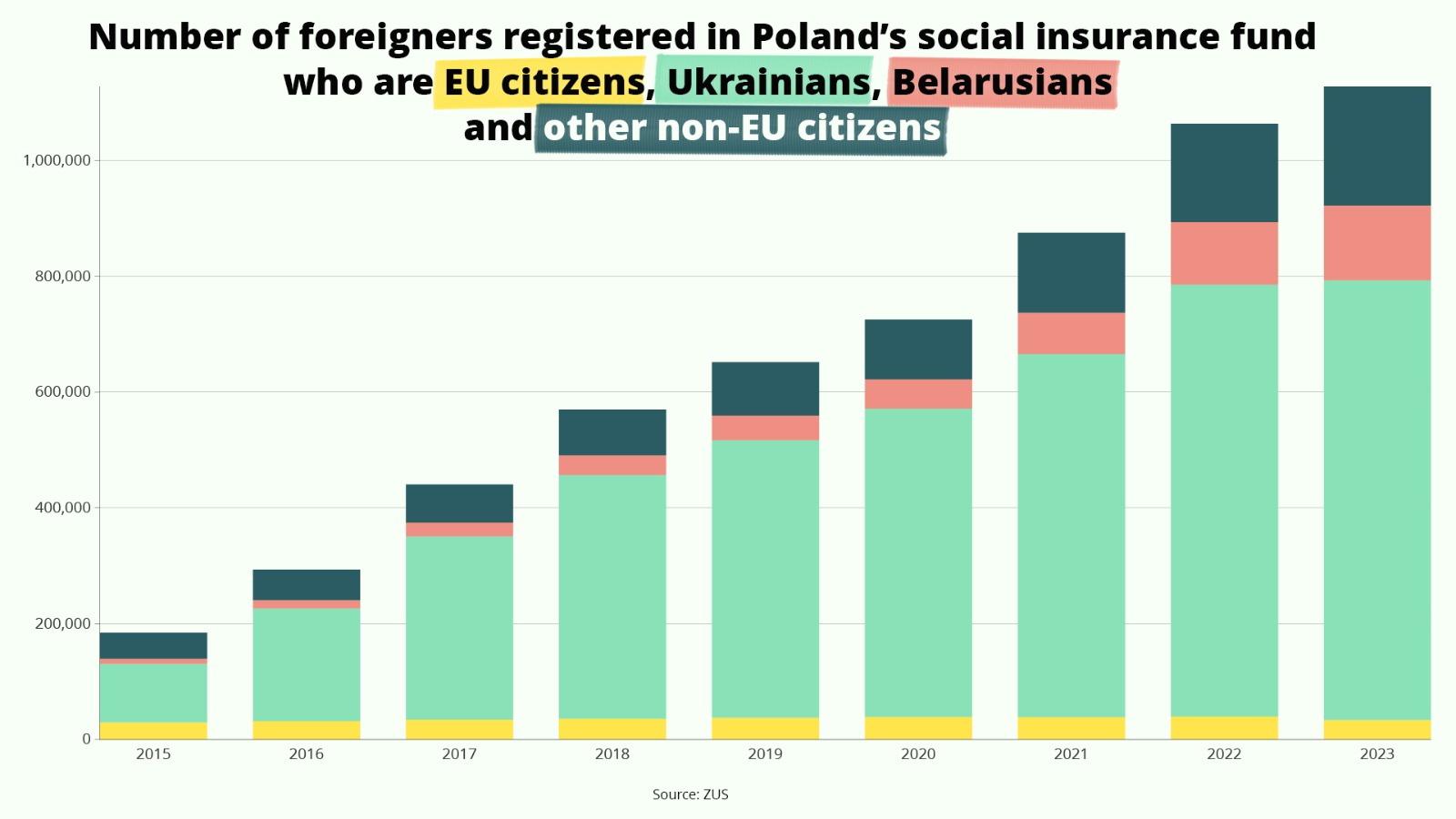

In practice, the vast majority of CIC clients are Ukrainians and Belarusians (Poland's two largest groups of foreign nationals, who collectively number between 1.7 and 1.9 million), and to a lesser extent, migrants from other countries, such as Georgia , Kazakhstan and Tajikistan.

How are the centers funded and operated?CICs are primarily funded through the EU's AMIF and European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), with a smaller contribution from Polish national and local funds.

Their total cost for 2025-2030 is estimated at around 374.8 million zlotys (€87.8 million), of which around 90% will come from AMIF. Regional costs vary, with the Mazovia, Lower Silesia and Silesia provinces planning to spend around 105 million, 43.3 million and over 40 million zlotys, respectively. On average, one single CIC will cost about PLN 2.17 million over five years.

While CICs are managed by Poland's interior ministry, they are operated by provincial-level governments (marshals' offices) in collaboration with local authorities and specialized NGOs.

Poland is already a country of mass immigration, but politicians have been reluctant to acknowledge it.

The last week has seen the start of a much-needed debate on how the country should respond to its new reality, writes @danieltilles1 https://t.co/566KjU7kd0

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 17, 2024

In accordance with AMIF recommendations and Poland's own migration strategy, each center is required to cooperate with at least one NGO experienced in serving diverse migrant groups, ensuring tailored support.

Sometimes those are local organisations, such as Fundacja “Koper Pomaga”, which operates one of the four CICs in Łódź. In other cases, nationwide NGOs, such as Fundacja ADRA Polska and Fundacja Ukraina, have run centres.

The centers were originally developed under PiSThe Polish right's scaremongering, which present CICs as part of a conspiracy against Poland's national interest, is particularly strikingly given that the first centers and the framework for how they operate were established under PiS, who were replaced in power in December 2023 by the current ruling coalition.

Despite its anti-immigration rhetoric, during its eight years in power, PiS oversaw immigration on a scale unprecedented in Poland's history and among the highest in Europe . Throughout that time, Poland was the member state that issued the most first residence permits to non-EU immigrants .

The concept for CICs in Poland was developed following study visits to other countries where similar centers operate, conducted between 2017 and 2020 at the request of the ministry for family and social policy, while the pilot program began in 2021.

The centers expanded significantly after Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 and were repeatedly praised by PiS politicians for the comprehensive support they provide to foreigners.

Following the opening of one of the pilot centers in Kalisz in March 2022, the then minister of family and social policy, Marlena Maląg, called CICs “a timely and significant project”, stating that “their establishment, apart from offering systemic support tailored to today's realities and needs, will also enable integration across many areas between foreigners and our country”.

So far, there is little indication that the protests surrounding the centers will have any impact on the initiative itself. New facilities are opening according to schedule, and those already operating are continuing their activities as usual.

It is likely that the anti-CIC panic will subside in the months following the presidential election and be remembered as yet another wave of anti-migrant rhetoric, weaponized for the purposes of a political campaign.

Main image credit: Adam Stępień / Agencja Wyborcza.pl

notesfrompoland

![A modern operating room in the Przemyśl hospital was ceremonially opened! A few days ago, the first modern stent implantation procedure in Poland was performed here [GALLERY]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fzycie.pl%2Fstatic%2Ffiles%2Fgallery%2F561%2F1660346_1750259023.webp&w=1280&q=100)