Uncertainty over certification affects possible 9/11-related illnesses coverage

When retired Nassau County Police officer Allison Beyerlein's routine blood work showed low levels of platelets – cells that help control clotting and bleeding – three years ago, she became concerned but never suspected doctors would find anything out of the ordinary.

When her platelet levels dropped so low that her doctor sent her to the hospital emergency room, she learned differently. Beyerlein was diagnosed with acquired amegakaryocytic thrombocytopenia (AAT), one of the rarest blood disorders in the world. The illness prevents her body from producing platelets, leaving her at constant risk of dangerous bleeding.

Medical literature has documented only about 100 cases of AAT worldwide.

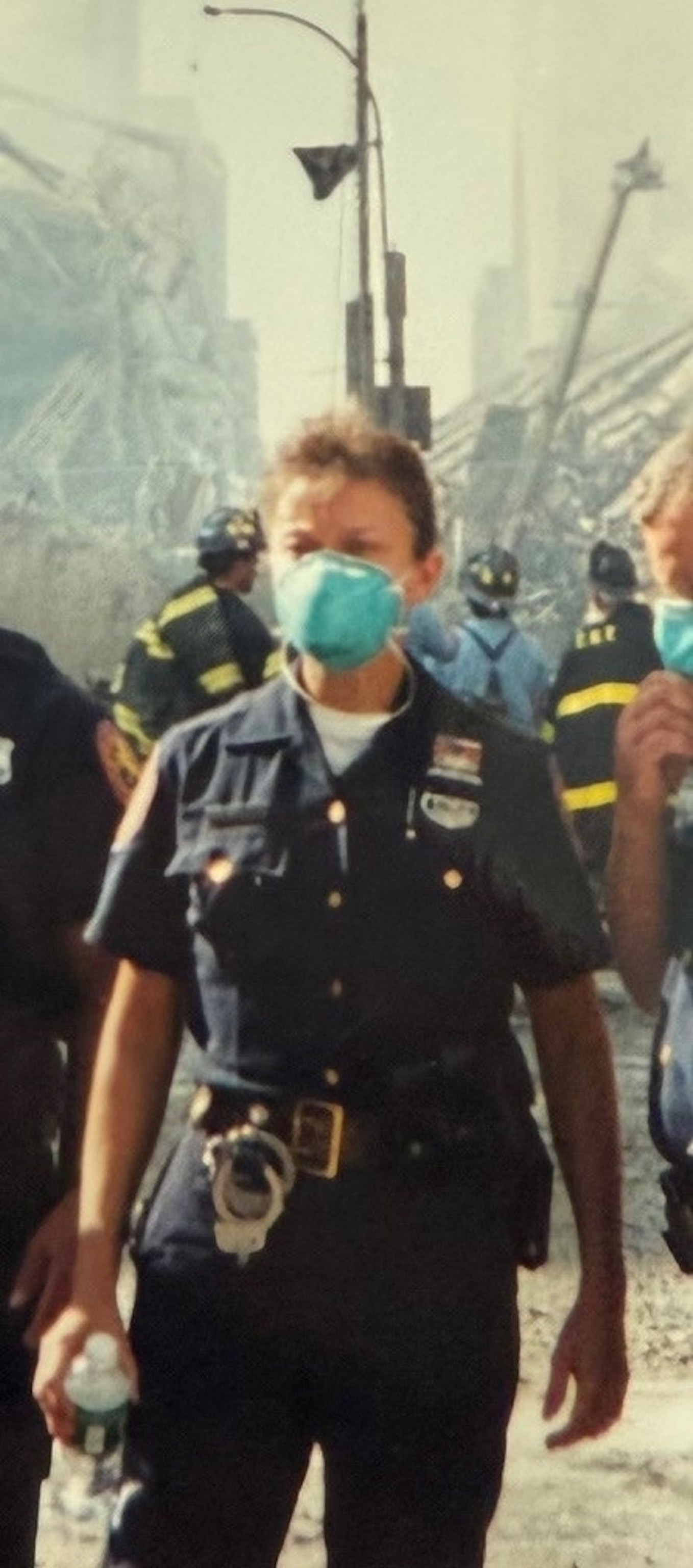

Beyerlein's case highlights a bigger problem. She was part of a team of first responders who spent weeks cleaning up debris after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. However, the World Trade Center (WTC) Health Program is neither reviewing nor certifying new illnesses that may be tied to Ground Zero exposures after the 9/11 attacks. That leaves patients with emerging conditions that could be related to such exposure, like Beyerlein, without program coverage or financial assistance.

“At first, I just couldn’t understand how something so rare could happen to me,” Beyerlein told ABC News. “It wasn’t until doctors started asking about my time at Ground Zero that I realized this might be connected to 9/11.”

Beyerlein said she first arrived at Ground Zero on Sept. 12, 2001, the day after the attacks, and returned there repeatedly over the course of months. She described her exposure to Ground Zero as "frequent and prolonged."

The WTC Health Program, created under the James Zadroga 9/11 Health and Compensation Act of 2010, provides medical monitoring, treatment and financial compensation for responders and survivors with conditions it has formally certified as linked to 9/11 Ground Zero exposure. Such certification means that the program determines that scientific evidence connects a disease to that exposure and subsequently makes patients eligible for treatment coverage and compensation.

Cancer, asthma and many mental health conditions are currently certified by the WTC Health Program. But AAT isn't certified, even though studies show that AAT can be caused by exposures to chemicals like benzene, a known toxin and carcinogen that was present in the dust and debris at Ground Zero.

This has raised concern among some advocates who say that AAT should be reviewed to determine if 9/11 Ground Zero exposure can play a role in a person developing the disease.

“This is exactly why we need a functioning review process,” said Ben Chevat, executive director of the nonprofit watchdog organization 9/11 Health Watch. “If rare diseases like Allison’s are showing up in responders, they should be evaluated without delay.”

While there may be other AAT cases among the 9/11 first-responder community, according to advocates, Beyerlein's is the only one substantiated. Doctors have determined that her illness isn't genetic, making environmental exposure a likely explanation for it.

Before the current administration, advocates, physicians and patients said that they would regularly meet with program officials to help gather data and evidence about new illnesses that might be added to the WTC Health Program's list of certified conditions. That data would then be reviewed by experts at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a federal agency that researches work-related health risks.

Although it’s often not possible to determine an exact cause of an individual’s illness, if the data showed a strong potential link to 9/11 Ground Zero exposure, the illness could be added to the official list of covered conditions under the WTC Health Program.

Many advocates, doctors and survivors of Ground Zero exposure who work within the program claim the review process is now stalled under a federally mandated “communications pause,” during which no new conditions can be considered for certification since there can be no presentation or discussion of evidence by NIOSH.

Advocates say that means the process to add new conditions to the WTC Health Program – including AAT, as well as some cardiovascular diseases, autoimmune disorders and cognitive problems – is at a standstill.

When contacted one week ago by ABC News, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said there is no communications pause and that the certification process is moving forward.

“There is no communication pause. That was lifted on February 1st and that was communicated down to all divisions,” the HHS spokesperson told ABC News. “The World Trade Center health programs and clinical centers are continuing to provide services to program members at this time and the program is accepting, reviewing and processing new applications and certification requests.”

Former Congressman Peter King, a Republican from Long Island, New York, and one of the earliest champions of the Zadroga Act, told ABC News that despite the HHS claims, there is effectively a communications pause in place during which no new illnesses can be certified under the WTC Health Program.

“HHS can call it what it wants. In practice, there is no communication at all with the 9/11 community. It just seems to me that it’s a stonewall,” King said.

He added that while illnesses like Allison’s might ultimately be found not to occur more often in 9/11 responders, every petition deserves a prompt review. Without it, for example, responders and their doctors cannot know whether emerging conditions may fit a larger pattern, said King.

“For patients, the uncertainty is almost as damaging as the illness itself and the longer the program remains silent, the more responders doubt its promise,” King said.

An ABC News request for comment sent to HHS regarding former Rep. King's claims did not immediately receive a response.

Ben Chevat of 9/11 Health Watch told ABC News that the WTC Health Program was designed to grow and adapt as new health problems surfaced among 9/11 responders, yet today it is stuck in neutral. Without active surveillance and timely decisions, the system risks failing those it was created to serve, he said.

Chevat and other advocates have pressed for action. In a recent letter Chevat sent to HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., he claimed that petitions have gone unanswered for months, surveillance of new conditions has stopped, and the program has not explained publicly how it is tracking conditions potentially linked to 9/11 Ground Zero exposure.

“The program must follow the requirements under the statute and make these pending determinations,” Chevat wrote. He told ABC News that he has yet to receive a response to his letter.

The last communication Beyerlein said she received from the WTC Health Program was in January of this year and did not offer coverage or compensation for her illness, but said they would contact her if “a possible WTC-related condition was identified.”

Without certification, Beyerlein cannot get WTC Health Program assistance paying her medical bills or receive other compensation for the toll her disease has taken on her life, should it be shown to have been caused by her Ground Zero exposure.

“I sacrificed as one of the first responders, but now I face an ongoing struggle just to have my disease recognized,” Beyerlein told ABC News. “This disease has changed everything about my daily life. I live every day knowing I could bleed without warning and yet the government can’t decide if I deserve care. It isn’t fair."

"I did my job at Ground Zero. Now they need to do theirs,” Beyerlein said

ABC News