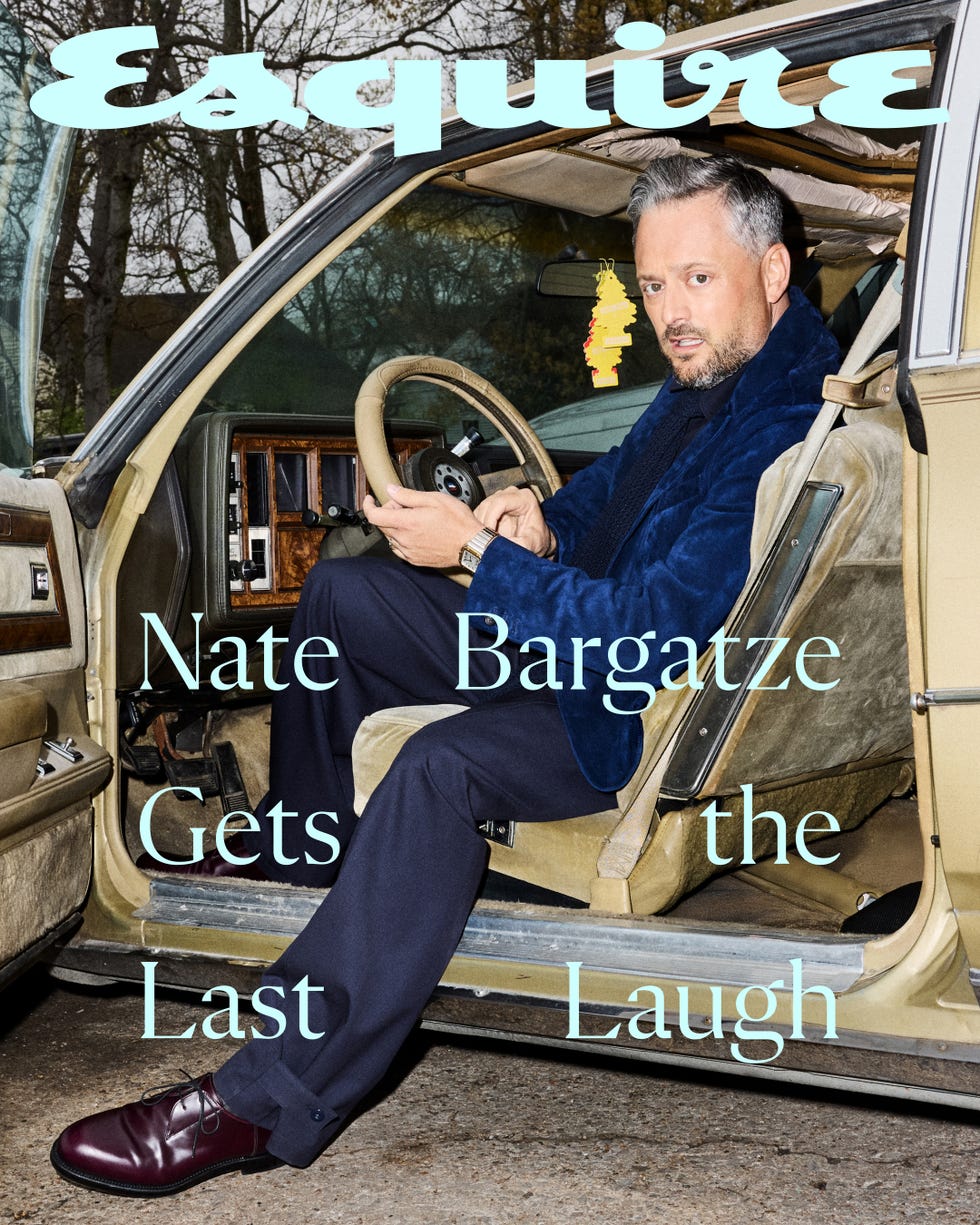

Nate Bargatze Gets the Last Laugh

Last year, Nate Bargatze, the forty-six-year-old comedian from Tennessee, sold more tickets to his stand-up shows than anyone else in comedy—including Jerry Seinfeld, Dave Chappelle, and Sebastian Maniscalco combined. That’s more than one million tickets for an $80 million haul. In October, he hosted Saturday Night Live for the second time in twelve months. Two months later, his third hour-long comedy special for Netflix premiered. Every week, you can hear his musing on the Nateland podcast. On May 6, his first book, Big Dumb Eyes, comes out, followed by another tour of arenas.

Bargatze is, quite simply, the most successful stand-up comedian working today.

Nate Bargatze, America's top-selling standup comedian last year, lives in the suburbs of Nashville. In April, Esquire photographed him around Nashville, including inside the Tennessee Titans stadium. Coat, jacket, shirt, tie, and trousers by Fendi Men’s; boots by Lucchese; Santos-Dumont watch by Cartier; rings by Bulgari.

Which is saying something, considering he’s a clean comic—no swearing, sex, drugs, or rock ’n’ roll. Politics is off-limits. Onstage, he’s an average middle-aged guy navigating the modern world of married with a child. His most famous joke is about ordering iced coffee with milk at a Starbucks and instead getting milk with ice. In sold-out arenas, where his shows consistently smash attendance records, he takes the stage almost as if by accident. Like he’s surprised so many people are there to see him. He heaps gratitude upon his audience. They love it. He goes down easy, like Xanax chased by a cool glass of iced tea.

Now this everyman spends large chunks of his days in meetings with Hollywood executives pitching him movies and TV shows. This month, he’ll begin filming his first movie, which he cowrote; he also plays the lead role. In September, he’s hosting the Emmy Awards. After grinding out a living for twenty years, telling family-friendly jokes, most of it outside the glare of the mainstream, Bargatze is in the white-hot center of the zeitgeist.

“I can’t overhype the guy,” says Jimmy Fallon, who’s had Bargatze on The Tonight Show more than a dozen times. “I don’t know how far he’ll go, but it’s endless for him.”

Here’s the plot twist: Bargatze is already preparing his exit from the stage.

Jacket by Savas; shirt, trousers, and tie by Todd Snyder; shoes by Pierre Hardy; Santos de Cartier watch by Cartier; ring by David Yurman.

Want more stories like this? Become an Esquire subscriber today.SUBSCRIBE

This isn’t some vague notion of going out on top. Bargatze knows when it will happen. “Two more tours,” he tells me. “I got this tour I’m about to go out on, and I want to do one more.” Bargatze figures he’ll wrap up his stand-up life in five years. He even knows the closer for his final set. After he delivers the joke: “Thank you, good night.” Exit stage left. Nate Bargatze, the stand-up comedian, will be done.

What comes next, he admits, is almost too audacious for him to say out loud.

Why is Bargatze only now, after two decades of consistent touring, exploding into the mainstream? Ask the suits. The Hollywood establishment passed on Bargatze more times than he can remember. While living in New York and then L.A. from 2005 to 2014, he pitched roughly ten sitcoms, filmed one pilot, tried out three times for Last Comic Standing, made it to the final round to be a Daily Show correspondent.

“I never got to do Letterman,” he says. “I got told I was too mundane. I had to look the word up. I didn’t know what it meant. It wasn’t good.”

Bargatze wanted those traditional Hollywood gigs badly. Nothing panned out.

“They have a system,” he says. “I like their system. I try to be in their system. And then I just kept getting told no, so I had to go create my own thing.”

VIDEOIn 2012, Bargatze and his pregnant wife returned to Nashville long enough to give birth to their daughter before giving Los Angeles a try. The family stayed for two years and moved back to Nashville for good. It wasn’t an act of surrender. In fact, he didn’t tell people he’d moved away from the West Coast, fearing it would signal he’d given up on show business. With a kid on the way, the Bargatzes wanted to be closer to family. Exchanging suits for roots would prove to be a savvy career move. From Nashville, he launched a stealthy assault on the very system that shut him out, slowly and methodically building himself into a juggernaut.

“I wanted to be great at stand-up,” he says. “I’m not trying to say I’m great, but I just knew I needed to figure out how to be great at this one thing and then the rest will come. That’s what’s happening now—you get a lot of stuff.

“You either make it at twenty or forty,” he adds. “No one makes it in the middle.”

We’ve all been there—the precarious middle, betwixt and between success and failure. And we’ve all experienced the sting of being passed over for a new job or a promotion, being told No, sorry, we’re going in another direction. The pain can linger, hardening into bitterness and victimhood. Some of us slink back to our hometowns, defeated. For Bargatze, the soul-crushing brush-offs lit a fire. Disappointment became the kindling, rejection the fuel. He built a worldview around proving the gatekeepers wrong. He didn’t turn lemons into lemonade; he said, I like lemons—what else you got?

“When you tell him no, he will say: Watch this,” says Felix Verdigets, Bargatze’s neighbor and friend, who recently became the CEO of his production company. “And he doesn’t care how long it will take to prove you wrong.”

As the culture lurches from an embrace of progressive causes toward one of social conservatism, the guy from Old Hickory, Tennessee, is showing everyone who him him no the lucrative opportunity they missed.

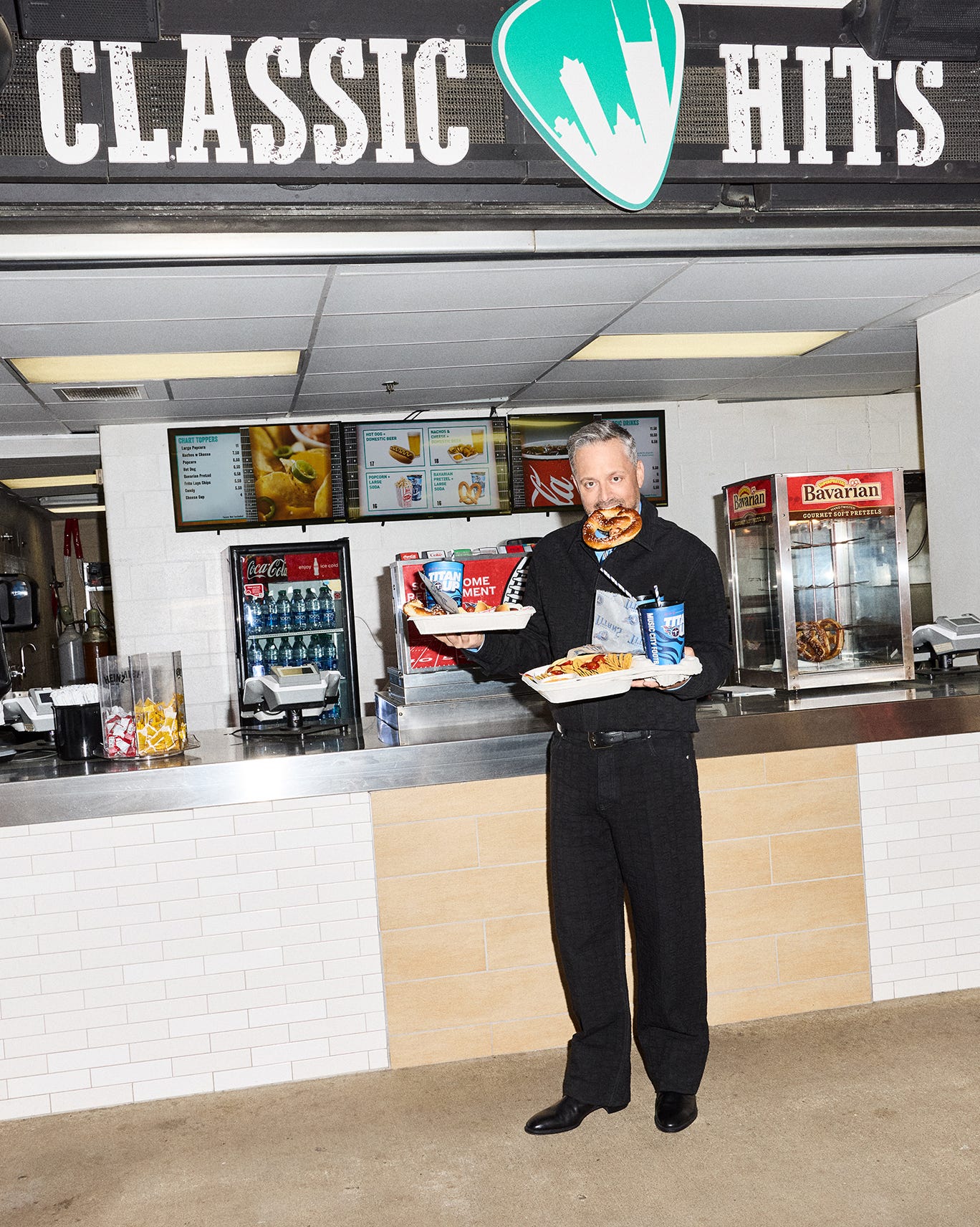

Bargatze plans to stop doing standup in the next five years to focus on his audacious plans for the future. Here, he's photographed inside Nissan stadium, where the Tennessee Titans play. Jacket, trousers, loafers, and tie by Gucci; shirt by Budd Shirtmakers; socks by Bresciani.

It’s a warm and wet Friday morning in April, and I’m in a cul-de-sac in suburban Nashville, standing outside a house where I’m told to meet Bargatze. As far as McMansions go, this is among the nicer ones: brick exterior, high ceilings, a pool in the backyard. I assume I’m standing outside Bargatze’s house. His assistant welcomes me inside and says Nate will arrive soon. Turns out this is not Bargatze’s home—he lives across the street in a nearly identical two-story—but he does own it. Friends and fellow comedians stay here when they come through Nashville. I guess it’s also where he hosts journalists.

A few minutes later, Bargatze walks over from the other house. It’s just after 10:00 a.m., and he’s dressed casually in an unbuttoned flannel shirt over a T-shirt, dusty pink jeans, and sneakers. He’s polite but low energy. Grabbing a Fiji water from the fridge, he settles into an armchair. I take the couch. He worked out that morning—a habit he’s trying to adopt—and soon comes to life.

“It all happens very slow, slower than you want, but faster than you think,” he says of his fame. “When it happens, you’re shot out of a cannon.”

“It’s like that line from the Hemingway book,” I respond. “He went bankrupt gradually and then suddenly.”

“Who’s Hemingway?” he says.

As with most Bargatze jokes, he’s the punchline. It’s a trademark of his humor; his onstage persona can be that of a dumb guy. He says he went to college for one year and earned zero credits. He doesn’t read books because they have too many words. Movies about history amaze him because he never learned it. “I watched the movie Pearl Harbor,” he said in his first SNL monologue. “I was as surprised as they were.”

Offstage, however, Bargatze is not a dumb person. His joke about Hemingway reveals this—it’s a sleight of hand: a sly way to puncture my literary reference. He’s put me on notice: Those big dumb eyes miss nothing.

“He’s got a gift of camouflage,” says Julian McCullough, an old friend and fellow comic, who emcees Bargatze’s arena shows. “He’ll be sitting in a room, and because of the way his face looks and the way he talks, people think he’s not picking up on everything. No one is more aware, or observing people’s behavior, more than he is. He’s like one of those stick bugs; you can’t believe it’s a bug because he’s watching the whole time.”

McCullough calls him a savant—so focused on observing human behavior he fails to notice the location of the water heater in his own home. In other words, even smart people are stupid sometimes.

Bargatze has learned to play it to his advantage. Inside this aw-shucks routine he finds the connective tissue in life, the moments to which most of us can relate—like when the coffee shop gets our order wrong—and making them funny. It’s won him broad appeal.

“Not everybody’s as original as they think,” Bargatze says. “You all have families. You all have this dumb stuff happen to you. You all think you’re dumb sometimes. That’s the only reason I have a career, because none of us are really that original.”

In an era when social media makes everyone the main character, a statement like this is borderline radical.

About twenty miles from Bargatze’s spare McMansion is his hometown of Old Hickory, once the site of a DuPont gunpowder factory. His family was “upper lower class,” he says, then pauses. “Or is it lower middle class?”

“My childhood was pure dumb funny,” Bargatze writes in Big Dumb Eyes, “but that pretty much only happened because my dad got all the miserable stuff out of the way.” His father, Stephen, had a traumatic childhood. Both of Stephen’s parents were alcoholics; his mom was abusive. As a teenager, Stephen ran away to Nashville, where he lived on the street for a few months until he tried taking his own life—“which he’ll tell you was the dumbest thing he ever did,” Nate says in his book. Just before Bargatze was born, his parents became born-again Christians, a decision that would ripple through his life and his career.

Bargatze on the streets of Nashville. Jacket and trousers by System; shirt and tie by Loro Piana; Classic Fusion King Gold watch by Hublot; hat by Nick Fouquet; belt by Kieselstein-Cord; pin by Wild Box.

Growing up with born-again parents meant Bargatze’s entertainment options were limited. They were “the most strict,” he says. The Simpsons, for example, was forbidden. But his dad was an entertainer—a magician whose trademark routine looks like an Andy Kaufman act. He puts on a straitjacket and asks a member of the audience to get him out of it. Audiences are left in stitches. Now Stephen opens for his son. In fact, his parents and his sister, Abigail, who works for Bargatze, occasionally go on tour with him.

Bargatze, the oldest of three children, got his dad’s entertainer genes and both his parents’ faith. He’s a practicing Christian. “I’m on the road so much, but when I’m here, I go [to church] as much as I can,” he says. Religion is an important part of his life. “It’s a good thing to be around,” he says. “I think it makes you feel grounded.”

It’s also rich soil for a comedian, but Bargatze approaches it from an unexpected angle. Unlike many stand-ups who were raised in the church, rejected it in adulthood, and lampoon their faith onstage, Bargatze unpacks the nuances of Christianity. “I had ’80s and ’90s Christian parents,” he says in Hello, World, his stand-up special on Amazon Prime. “Well, that’s the most Christian you can get of the Christian. I think Jesus had more fun than I did.” These aren’t just church jokes, the comedian and podcaster Marc Maron points out when we talk. Bargatze resembles the Jewish or Muslim comedians who make religion a part of their identity without turning it into faith-based humor. And the material plays well to even the most devout Christians, many of whom make up his legions of fans.

Add to that the fact that Bargatze is sober. He says alcohol stood in the way of moving his career to the next level, and he gave it up in 2019 when he made the move from clubs to theaters. “I did not have a control on it to … I would go too hard with it,” he says. “But I knew, if I want to go where I want to go, this is in the way.”

Does he miss it? “I think I miss the relief of drinking,” he says. It quieted his racing mind. Now golf helps. “I tell a lot of comics: ‘If you want to do something, you’ve got to really obsess over it,” he says. “That’s not always fun. I mean, that means you wake up to go pee in the middle of the night and you’re thinking about comedy.”

He admits, somewhat reluctantly, that he can be an anxious person. But he tries to channel the anxiety into his comedy. “If I’m going to be obsessive over something, then I’ll use it to my advantage,” he says.

Many of the stories Bargatze tells onstage are about his wife, Laura, whom he met at an Applebee’s in Tennessee where they both worked. They’ve been married nineteen years and have one daughter, Harper, who’s twelve. Bargatze fans know her as the little girl who introduces her dad before stand-up specials. And those fans have likely noticed the dearth of jokes about Harper lately. “I’ve backed off a lot on my daughter,” he says. “She’s at the age where kids are going to pick on her or say something.”

As for Laura, he has a strategy for writing material about their marriage. “You’ve got to show love,” he says. “If I want to talk about my family, you have to believe that I love them, or I’m the worst person ever.” He didn’t understand that at the onset of his career and could feel the audience’s uneasy reaction to his edgy jokes about Laura. They needed to know, “This is a happy couple; that’s a typical fight.”

Bargatze pops his head out of the door of Zanies comedy club in Nashville. Coat by Jil Sander; shirt and tie by Emma Willis.

“If I want to make fun of something she did, I need to also be the reason that she did it—it’s my dumb reason,” he says.

Treading carefully with his family has done more than keep the peace at home. Telling wife jokes can veer into hack territory fast, earning a comic the dreaded label of “wife guy.” That doesn’t win you an SNL monologue. Achieved with a precision that feels effortless onstage, it’s family-friendly humor that also works in New York.

When Saturday Night Live announced on October 17, 2023, that Nate Bargatze would host its next the show, media hives on both coasts let out a collective Who?! Hollywood was still on strike, and Bargatze’s appearance was dismissed as a stopgap measure until the show could start booking A-list celebrities again. The most jaundiced commentators sneered with the suggestion he might be … a Trump supporter.

But it wasn’t just the media elite who were confused. One of the top searches on Google leading up to his SNL appearance was “Who is Nate Bargatze?” He realized the stakes—hosting the show was one of those rare moments in life in which success will vault you to the next level. “I knew I had to destroy in this monologue,” he says. “I knew it was a welcoming, a hello.”

Mission accomplished. The monologue, a greatest-hits collection from his career and one of the longest in SNL history, turned skeptical viewers into Nate Bargatze fans. His episode, at the time it aired, was the highest rated of that season. The actor and podcast host Will Arnett said “Washington’s Dream,” in which Bargatze portrays the first president of the United States and lampoons America’s odd system of weights and measures, was the best SNL sketch in fifteen years. The website IndieWire published an oral history dedicated to the sketch.

Jimmy Fallon, who introduced the idea of Bargatze hosting to SNL boss Lorne Michaels, had no doubt he would succeed in front of a national audience. “I think he’s the guy,” Fallon told Michaels. “I know he’s kind of an unknown, but I’m telling you, he will score.”

The hosting gig introduced Bargatze to a broader audience, but he had been performing in clubs, theaters, and outdoor venues, in markets big and small, since the early 2000s. He’d appeared on Late Night with Conan O’Brien and The Tonight Show. SNL helped him land arenas. In this rarefied air, he continues to hone his act, seeking perfection. “A joke might kill in an arena, but if an element feels off, he’ll start tweaking it,” McCullough said. “I don’t know any comic at his level who is doing that.”

Of course, it’s all family friendly. Dirty jokes never even occur to Bargatze when he writes. “I don’t think I’ve ever thought of a sex joke,” he says. Offstage, he avoids swearing. And then there’s politics, which you won’t hear at a Bargatze show.

“If I want to give you my opinion on who I voted for, who’s that for?” he says. “It’s for me, really, because I want you to know I’m smart. I don’t think it’s really helping an audience. You don’t think they know who to vote for? They’re living life.”

He adds: “Once you run out of celebrities’ opinions on politics, maybe I’ll jump back in, but right now I just want to do the opposite.”

In a bitterly divided country, Bargatze wants to be the place where audiences can turn their brains off. And the audience for Bargatze is the entire family: moms and dads, children, grandparents. “I need you to be able to trust that when your kids are in the car, you can play my album and you’re not having to think, Let me make sure there’s nothing I don’t want to have a conversation about right now. There’s a trust.”

Jacket, shirt, and trousers by Canali; boots by Lucchese; hat, Worth & Worth by Orlando Palacios; pin by Lady Grey.

“He’s coming at a time where comedy in some ways is in trouble,” says Maron, who noticed Bargatze at a comedy festival in 2012 and eventually brought him on as opener. “You have these very tribalized camps of comedy, the anti-woke crew bravely speaking power to truth, and he sort of transcends that.”

You may never know how Bargatze votes, but he’s attentive to what’s going on in the world. And the public’s adoration of him and Hollywood’s sudden embrace does reveal something about our culture. Maybe it’s a retrenchment toward so-called family values. But a broad audience has shown that it wants entertainment that’s easily digestible, apolitical, and preferably about a place that isn’t along a coast. The entertainment industry is eager to provide it, and Bargatze is certainly profiting from the cultural shift.

Bargatze tells me a joke about getting asked to host the Emmys. “Why did they pick me to do it?” he says. “Well, the election probably helped.” It got Hollywood executives asking: “Who doesn’t live in L.A.? Who’s available?”

Maron sees it another way.

“He’s bigger than what’s going on socially,” Maron says. “Because of his talent and point of view and the way he does comedy, which is truly unique, he would’ve been a big star no matter where the culture is.”

So what is Bargatze’s plan now that he has Hollywood’s attention?

He’s going to build his own media empire.

Seriously.

When I ask Bargatze about his influences, he lists four people. Three of them are comic luminaries: Jerry Seinfeld, Judd Apatow, and Adam Sandler. This makes sense of course. The fourth person he mentions is Walt Disney.

What’s that all about?

According to Bargatze, Walt Disney—the man, not the brand—loved everything he made, and cared about his customers. “Now Disney is run by a guy that’s just a businessman,” he says. “Well, that guy doesn’t care about the audience.” Bargatze cares deeply about his audience. He sees himself as their servant. “None of this happens without them,” he says of his career.

When he was still grinding it out, lost in relative obscurity, he’d see his peers remark on a controversial issue, often something political. “They would skip a bunch of steps,” he says. “Now they’re mentioned everywhere because they said something crazy. Now Netflix called them and they got a special.” Bargatze was tempted. He considered going that route, but he resisted the urge. Otherwise, he might lose his audience’s trust.

“The hardest thing to do is to stay that path because it’s not as flashy,” he says. “You got to just sit in it. You got to slowly keep going. Then you get to the point where I’m at now. I’m frustrated by an entire system that’s like, ‘Y’all were just grabbing headlines,’ when I felt like, ‘Why did y’all not look at me more?’”

He uses this word frequently: frustration. Bargatze is frustrated that much of the entertainment industry—the system—didn’t recognize his talent sooner. He’s grateful to the few big names who gave him a shot: Fallon, Michaels, CBS CEO George Cheeks, who tapped him to host Nate Bargatze’s Nashville Christmas last year. But for years, Hollywood wanted viral takes over Bargatze’s everyman humor.

His audacious plan after stand-up is to be the next Walt Disney and Mickey Mouse, the creative genius and the face. He’s going to make movies and TV shows, mint merchandise, publish books, produce podcasts, lend his name to cruise lines, and create a farm system for young comedians.

“If you’re working hard, and you’re clean, and you’re really funny, and you’re just not getting noticed, he’ll give you some help, some encouragement, the idea that at least you’re getting somewhere,” McCullough says.

Perhaps his boldest plan is to build a theme park in Nashville called Nateland.

“I’ll be honest with you, I bet we’re closer than people think,” he says about the park. “But it’s still a little bit of a ways off.” He’s in the market-analytics phase of the project and knows where it will go: the site of the former Opryland theme park, where Bargatze had his first job.

Jacket and pants by Ferragamo; shirt by Emma Willis; tie by Brooks Brothers; boots by John Lobb; belt by Tecovas.

Before Nateland the theme park becomes reality, he needs to build the rest of the business, which is called Nateland Productions. There are about a dozen full-time employees now. Until a year ago, the CEO, Verdigets, who has four degrees, including a Ph.D., in addition to being Bargatze’s neighborhood pal, was a partner at the prestigious consulting firm KPMG. He buys into Bargatze’s vision.

“Entertainment seems to me in this mode of heartland, a word that’s been overused a bazillion times,” says Verdigets. “Everyone is capitalizing on it right now, and some of it is going to feel inorganic. What’s going to separate our content is that this is how we’ve always done it. It’s very authentic, it’s very organic.

“What Disney has is Mickey Mouse,” he adds. “What Nateland has is Nate.”

Sure, many celebrities reach a certain point and start a production company. The difference between Nateland and everyone else is the scale of ambition (a theme park?) and its selling point: family entertainment that isn’t pigeonholed into kids-only programming or faith-based content. Comedies, dramas, romances, you name it—all marketed for a mass audience. It’s a restoration of the entertainment ecosystem Bargatze remembers growing up with in the ’80s and ’90s, like the TGIF slate of shows on Friday nights. Entertainment the whole family can enjoy together—the kind his strict born-again parents allowed him to watch.

“I don’t think anybody’s even trying to make stuff for everybody,” he says.

To illustrate his point, Bargatze brings up Succession, the HBO family drama about an elite, dysfunctional family in New York. “I did not watch Succession,” he says. “I know it’s the greatest show ever to exist. I’m not a moron. Everybody understands it’s the greatest show in the world. I want to watch it. This has nothing to do with the show. But no one watched it in the grand scheme of things.”

That’s not exactly true. The show was a critical and awards-season darling that ran for four seasons. Its most-watched episode—the series finale—drew nearly three million viewers in 2023. Not bad, but the most recent episode of Survivor had more than four million viewers. Almost five million people watched Bargatze’s first appearance on SNL. In the streaming era, comparing audience sizes can be apples to oranges, but Bargatze’s point is this: A hit show should have more people tuning in.

“Everybody has lives, everybody has kids, everybody has stuff to go do,” he says. “They don’t want to sit and worship your art. There’s got to be a balance of appreciating Succession and appreciating King of Queens. Those worlds have to exist together. Now you have too many Successions. There’s nothing that’s a palate cleanser.

“You know what?” he continues. “Maybe the Successions are a little bit easier to make because you’re making it for such a specific audience. You get the runway to make it for five, six years because it’s cool. What if no one watches? It doesn’t matter.”

The shows and movies that everyone watches? Well, King of Queens, plus Everybody Loves Raymond, Home Alone, Planes, Trains and Automobiles. “Those are the ones you go back to,” he says. “Those are the ones that are hard to make.”

Bargatze has diagnosed the problem. We live in a highly fractured media environment, with entertainment geared for specific audiences, rarely for everyone. Unless it’s a sporting event, families don’t gather around the TV. They’re affixed to their own devices. Fewer and fewer people go to the movie theater.

Bargatze believes he can offer the remedy. I challenge him on this assertion. Isn’t the genie out of the bottle? Aren’t audiences trained to look at their phones and consume their own media? The entertainment to which Bargatze refers seems anachronistic, like a billionaire believing he can revive his hometown newspaper.

“I don’t think so,” he says. “I think there’s no one trying to do it. People still go to concerts. I do shows in front of 15,000 people who are laughing and paying attention for an hour. I see it in every single city. People want to go do something, and you’re just not giving them something to go do.”

Plus, there are more than 1.3 million data points that suggest this idea will work, Verdigets says, referring to the number of tickets Bargatze sold last year. “If people are willing to spend $100-plus on a ticket ... and that's one person sitting on a stage for sixty minutes talking,” he says. “Imagine what we could do at $22.50 a ticket with a big production, a lot of visual effects, sounds, lights, and motion picture.”

Next March, Bargatze’s theory will be put to the test with the premiere of The Breadwinner, which Bargatze cowrote with Peabody Award winner Dan Lagana. It’s based partly on Bargatze’s life and stand-up material, and according to Bargatze, it’s “kind of like Mr. Mom,” the 1983 comedy starring Michael Keaton—one of those movies people rewatch.

All of this—the movies and TV shows, the farm system for up-and-coming comedians, the Nateland theme park—is a result of Bargatze being told no. “I just want it in my own hands,” he says. “I'm tired of it being in other people's hands that can say no.”

“I’ve had to build myself up to this crazy level just for them to say, ‘All right, let’s maybe let you do a movie,’” he explains. “I’m like, ‘What? I don’t even know if I need it.’ And they say, ‘Well you want to do TV now?’ And I’m like, ‘What? Are you crazy? The whole point of you is that you’re supposed to help me get to the point that I’m at. That’s why you do TV, to get to this level. Y’all let me get to this level without you.”

He pauses a moment. “Now I don’t want to go back unless it’s moving my goal forward of Nateland,” he continues. “So now everything I do is about moving Nateland, the company, forward.”

His plan extends well into the future: After stand-up, he’ll appear in and help write movies and TV shows for about five to ten years, with maybe a Tonight Show set when he feels like it. Then he’ll recede from the public view, overseeing Nateland and handing over the mantle to other comedians.

Jacket, shirt, and trousers by Prada.

Once he’s done telling me about Nateland, Bargatze admits it’s all a little embarrassing to talk about. It's difficult to share his outsized ambition. There are people who will say: “Who are you to think you can do this?” Even for the country’s most-successful comedian, the years of rejection are hard to shake. And for the guy from Old Hickory, so are the spoils of success.

The other day, Bargatze picked up his daughter from school in the Bronco he owns. She prefers the Bronco to their other car, a Mercedes-Benz, because riding in the German car might lead other people to say the Bargatzes are rich. Bargatze gets it. He’s proud of his hard work and the wealth and success to which it's led. He had none of it growing up. But, he adds, “I can feel embarrassed by the stuff that I have, that I can afford, that I can go do. It’s materialistic and none of it matters.

“The hard part is trying to land in the middle,” he says. “To go, I need to be doing this for the right reasons. I need to be doing it...” He trails off for a moment.

Recently, Bargatze started seeing a therapist, which is new territory for him. He doesn’t like talking about therapy, but he knows it helps. What he’s experiencing is difficult terrain to cover with his friends. “I talked to my therapist today exactly about this. How do you balance that?”

For better or worse, Bargatze will have plenty to distract him. The tour he’s about to begin, the movie, and, of course, all the work to build Nateland into the next Disney. And then there’s his final stand-up special and that last joke he’ll tell. It’s about his daughter. He won’t share it with me—it’s not ready for public consumption because she’s not ready to hear it. In five years, he figures, he can talk to her about it.

“I need to wait until she understands the story, the idea behind it,” he says. “It’s nothing bad. I just need to make sure she knows it’s not coming from a place where you’re making fun of them.”

He needs to hear yes. Then the next phase of his life begins.

Photographed by Jeremy Liebman @jeremy_liebmanStyled by Alfonso Fernández Navas @alfonsofnHair by Eric Miller @thetourbarberGrooming by Katie Kendall @beautybyk2Production by Katherine Prato @katherinepratoproductionsTailoring by Jason Jarrett @jchristopher_jarrettVisual Director: James Morris @j_alexander_photoExecutive Design Director: Martin Hoops @mhoopsdesignEntertainment Director: Andrea Cuttler @angcutt

Special Thanks to Nissan Stadium @nissanstadium @titans

esquire