Reimar Gilsenbach | A forgotten admonisher

Where the village of Marzahn once stood, a satellite town of (East) Berlin was built in the 1970s." This is how a text by Reimar Gilsenbach from 1986 begins. The new blocks of flats reached right up to the S-Bahn line. And beyond the tracks at the then S-Bahn station Bruno-Leuschner-Straße (now Raul-Wallenberg-Straße) lay the cemetery, its high fences resembling an old estate park, in the middle of wasteland. Right there: "A few hundred meters away stand three chestnut trees."

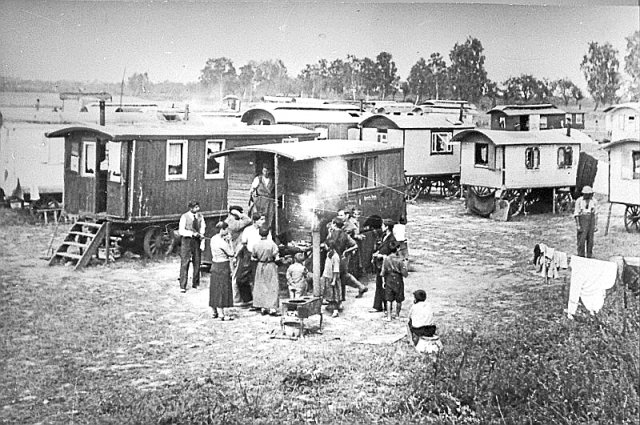

This group of trees occupies a central position in Gilsenbach's books. Three trees in an open space, which, as in a story by Ingeborg Bachmann, bore no fruit and were certainly already red and brown in the first days of October, as if aflame in autumn, a torch dropped by an angel. They were a memorial sign marking the place where Hitler first had members of a "non-European alien race" ghettoized. Reimar Gilsenbach wrote of the 1,200 people who were tortured here: "For nine years, Sinti from Berlin lived and suffered here in bondage. Nothing remains to remind us of it. However, anyone who walks attentively from the three chestnut trees to the cemetery and searches the ground might find a handful of shards. Shards of cups, porcelain dolls, and knick-knacks, shards of German history, witnesses to an unpunished and unremembered crime."

Commitment to recognitionThe Marzahn "Gypsy camp" had never been mentioned in literature about the Nazi era until then. Gilsenbach considered this no coincidence; he saw it as a legacy of the "Third Reich." After the war, no one boasted about having hidden a Sinto or helped one escape. Hitler knew very well why he first targeted the weakest of the groups destined to fall victim to the planned genocide. "And the anti-fascists?" asks the author. "Everything remained silent. As expected, no one expressed solidarity with the 'Gypsies.' Not to this day!" At least 200 Sinti are known to have been deported from the Marzahn concentration camp to Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp in March 1943. Of them, only seven survived, among them Otto Rosenberg, father of the pop singer Marianne Rosenberg.

According to historian Patricia Pientka, the persecution of the Sinti and Roma was long viewed not as racist, but as crime-preventive persecution in both German states. In the GDR, however, Reimar Gilsenbach was able to achieve, through his personal commitment, that formerly persecuted Sinti were also recognized as victims of fascism. For example, Sintiza Agnes S., who was interned in the Marzahn concentration camp from May 1936 and, even after the end of the war, had to live in the semi-ruined camp barracks for three and a half years. It was not until January 1949 that she was given her own apartment. And because the Berlin Committee of Anti-Fascist Resistance Fighters did not consider the internment in the Marzahn camp to be concentration camp imprisonment, it refused to recognize the woman as a victim of the Nazi regime. Gilsenbach writes: "In 1967, I succeeded in having the Marzahn camp classified as a concentration camp-like concentration camp. I helped Agnes S. to submit a new application” – successfully.

Communist with good contactsReimar Gilsenbach (1925–2001) was a writer and journalist. It is thanks in no small part to his dedication that the memory of the forced labor camp is now an important part of the culture of remembrance in the Marzahn-Hellersdorf district. Indeed, the first official commemoration event at the end of June 1986 was his initiative: a rather stiff and ritualized commemoration, as Patricia Pientka, herself a Sinteza, describes in her book on the Marzahn forced labor camp, but which resulted in Gilsenbach being able to publish the first articles about the camp. Finally, the GDR media reported on it, albeit on a rather modest scale. And Gilsenbach, who, like few others, made a greater effort to preserve remembrance, has now fallen into oblivion.

In the Stasi files, specifically in the opening report of the "Schreiber" operational case dated May 29, 1984, the following information about him is stated: "In recent years, G. has published several books that quickly sold out. Among the most recently published books and new editions are the children's books 'Around Nature' and 'Janitschek in the Robber's Castle,' as well as a major circus novel with a total circulation of 600,000 copies. Currently, G. is working intensively on the history of the Roma and Sinti."

By today's book market standards, Reimar Gilsenbach was a bestselling author who was also committed to human rights and the environment. This makes the Stasi's assessment at the time all the more astonishing: "G. evidently intends to achieve fame, which he cannot achieve through his literary work." Gilsenbach was a "contact person for the well-known Havemann and Biermann," who called themselves "communists" and, from this position, considered themselves "critics of the system." "It cannot be ruled out that G., also considering himself a communist, acts and plans his activities in ideological agreement with Havemann's views. It cannot be ruled out that he is inspired and controlled by hostile forces."

The MfS (State Security) district office in Eberswalde-Finow investigated Gilsenbach under Sections 220 and 219 of the GDR's Criminal Code, i.e., for "publicly denigrating state bodies and social organizations" and "illegible contact" with organizations, groups, or individuals operating against the state order of the GDR. These charges carried up to two or three years in prison, respectively. However, it never came to that. Apparently, Comrade Gilsenbach had good connections to the upper ranks, all the way up to Honecker. The same OV file contains a note stating that his approved trips to the West "have the general approval of the Office of the Chairman of the State Council and General Secretary of the Central Committee of the SED." When, in the mid-1980s, the child of a Sinti family was arbitrarily placed in a home – the boy had been repeatedly insulted and bullied in class because of his origins – it was not least Gilsenbach's letters to Erich Honecker (his wife Hannelore protested at the same time to Margot Honecker in the Ministry of Education) that brought the boy back to his parents.

Strong ecological interestIn his posthumously published autobiography, "Whoever marches in lockstep is going in the wrong direction," Gilsenbach writes: "I was born in September 1925 among freely practicing anarchists," in a kind of rural commune in the Ruhr area. He writes of reform fashion, a passion for nudity and unfettered love, the first eco-freaks, Wandervogel songs, and "wandering birds on sandy heaths"; of a mother who raved about everything good and beautiful and a father "so anarchistic that he didn't even join an anarchist club." How much of this is true is difficult to say, only that it is part of the essence of writing to bring oneself into the world anew.

In his memoirs, Gilsenbach then lists further milestones in his life: the Jungvolk (Young People), Hitler Youth, Reich Labor Service (Reichsarbeitsdienst), Wehrmacht (Wehrmacht), imprisonment, and the National Committee for a Free Germany. In 1947, he returned to Germany and completed his Abitur (high school diploma). The handbook "Who Was Who in the GDR" states that he was an editor of the "Sächsische Zeitung" until 1949, when he was summarily dismissed for political reasons. This was followed by a ten-year position at the Cultural Association's magazine "Natur und Heimat" (Nature and Homeland). This work sparked his interest in ecological issues. The writer, who lives in Brodowin, was a member of the Central Commission for Nature and Homeland of the Cultural Association until 1989, as well as on the central board of the Society for Nature and the Environment. In 1981, he founded the "Brodowiner Gespräche" (Brodowin Talks). One of the participants, the peatland ecologist Michael Succow, recalls: "It was a movement that united bright minds who wanted to reform the GDR system."

Finally, during the fall of the Berlin Wall, Gilsenbach was one of the founders of the GDR's Green Party. A few years earlier, the Stasi claimed to have observed that Gilsenbach's "strong ecological interest" was increasingly coming into conflict with the socialist social order because he overvalued ecological ideas, thus emphasizing certain tendencies toward overexploitation and believing them to be inherent in the system. His basic attitude and motivation could not be clearly classified. His "political ambivalence" was expressed in the fact that he increasingly used reactionary and hostile circles within the Protestant Church and so-called church peace circles to advocate his positions. Michael Succow explains Gilsenbach's message in simple terms: "If we leave nature unchanged, we cannot exist. If we destroy it, we perish." The narrow, ever-narrowing line between change and destruction will only be successful in the long run in a society that feels at one with nature.

On September 16, Reimar Gilsenbach would have turned 100 years old.

On Saturday, September 20, 2025, the Alliance for Democracy and Tolerance will commemorate Reimar Gilsenbach with readings, discussions, and concerts at the Mark Twain Library in Marzahn-Hellersdorf starting at 3 p.m.

nd-aktuell