Exclusive: Exploitation of apprentices | From recruitment to training to exploitation

"The training system in Germany is a model of success." This is what it says on the website of the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. And: "Because the German economy needs well-trained specialists, careers with vocational training are more promising than ever."

At the beginning of June 2025, Thuy Tien Vu (name changed) – wearing glasses, a gray quilted vest, her hair tied in a short braid – was sitting in a counseling center in eastern Berlin. Here, on Storkower Straße, counselor Thanh Dam supported people like Vu who had questions about careers and training. Starting an apprenticeship as a restaurant manager hasn't opened up any bright prospects for the 35-year-old so far – quite the opposite: She experienced exploitation in a hotel in a small town in central Germany. Vu even left her home country and paid a lot of money to come to Germany, where the training and job market enjoy a good reputation. This applies even to people like Vu, who have already completed a degree in Vietnam.

Vu belongs to a growing group in Germany. She is one of tens of thousands of (mostly) young people who have been recruited from third countries for dual vocational training – many of them through private placement agencies that operate largely unregulated, contributing to cases like Vu's being commonplace. Third countries are defined as countries that are not part of the EU.

"Then who's going to work here tomorrow?"Vu's story in Germany begins in September 2023. She arrives in Frankfurt am Main by plane from Saigon, excited and hopeful. A few months before leaving Vietnam, she received a training contract and learned what profession she would be learning in Germany and where. At Frankfurt Airport, Vu is greeted by three men. They introduce themselves as employees of the German partner company of the placement agency with whose help Vu had applied for a training position – and first demand money: 2,150 euros, a kind of "deposit," as they say. Vu had already paid 2,500 euros in Vietnam. Then she boards the train and shortly afterwards reaches the hotel where she will live and work for the next few months. There are a good 100 beds, around ten employees, and nine trainees, eight of whom were recruited from Asian countries.

In the months that followed, Vu's positive image of Germany would change dramatically. She spent more time cleaning the rooms or doing odd jobs in the kitchen than in the hotel restaurant. The hotel also had Vu sign a "loan agreement" for a (low) four-figure sum to repay the "expenses fee for the agency arranging the training placement" and the "transfer costs," as the contract states. Vu was to repay the amount plus interest in twelve monthly installments—her payslips show that these installments were deducted directly from her training allowance. The loan agreement also stated that the "entire outstanding amount is due for immediate repayment" if the training contract ended "before full repayment."

The tone in the hotel is also harsh. According to Vu, excessively long working hours and threats of dismissal are part of everyday life. One day, she has to go to the hospital. Her boss objected and asked her, "Who will work here tomorrow then?" Only at the insistence of a Vietnamese fellow trainee did she finally receive medical attention. The boss could not be asked to comment on this incident to protect Vu's anonymity.

The "full-service package"The hotel where Vu is beginning her apprenticeship isn't the only one recruiting for trainees abroad. In recent years, the recruitment of skilled workers has led to a veritable rush to encourage young people to pursue vocational training in Germany. Companies in all sectors, but especially those with low wages and harsh working conditions, such as the hotel and hospitality industry, are looking for trainees in Vietnam, Morocco, India, and other countries. Accordingly, the number of those living in Germany with a residence permit for vocational training is rising: these are those who have applied for training in Germany from countries outside the European Union. There were approximately 34,000 at the end of 2022, and 55,000 at the end of March 2025.

To attract this sought-after young talent, the federal and state governments are entering into numerous partnerships with third countries. However, programs with names like Apal (training partnerships with Latin America) or Mazubi (apprentices from Morocco) are insufficient to meet the growing demand for trainees. Thus, a growing market of private placement agencies has emerged in the wake of these initiatives. There is no certification requirement for them in Germany; essentially, anyone can open an agency. The promise: to ensure that companies willing to provide training find each other and potential trainees from abroad, and to bring them to Germany.

These services aren't free. Many agencies charge companies for a "full-service package"—candidate search, placement, language course, language certificate, visa, and flight. The agencies and/or—as in Vu's case—the training companies often pass on these costs to the trainees.

In Germany, trainees may not be charged any money for the mere placement of a training position – but in their home countries, such as Vietnam, the young people's families often pay five-figure sums for an apprenticeship in Germany. If an agency is based there, this is not illegal. Furthermore, contracts concluded in addition to the training contract – such as Vu's "loan agreement" – in which no placement fees are explicitly passed on to the trainees, but rather "recruitment costs," for example, for transfers, language courses, and visa acquisition, are legal or at least fall within a legal loophole. Despite numerous attempts, no placement agency was willing to discuss the matter.

When contacted, the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (BMAS) stated that it had "no representative findings on the costs incurred in the recruitment of trainees from third countries by private employment agencies." However, such cases were known from "press reports and discussions with various stakeholders in the field of skilled labor recruitment." The fact that fees are paid by those recruited is also evident in posts in Facebook groups such as "German Information Portal on Vocational Training," with 40,000 members, or "Study & Training in Germany," with more than 100,000 members. It is not uncommon to read there how anonymous users already in Germany complain about exploitation, excessive working hours, harassment, or racism, or even look for "contracts," i.e., training positions. Some users limit the amounts, for example, asking for contracts for less than €2,000. A 2024 study by the Free University of Berlin states: "As a rule, the language and placement service for a trainee from Vietnam to Germany costs around 12,000 euros." This is an enormous sum, given that a good average salary in Vietnam is 230 euros per month.

Vocational schools left alone"In order to gain access to the German skilled worker program, they must invest a significant sum of money, which they are expected to work off as debt during their training. This puts considerable pressure on them." This is also stated in the anonymous evaluation of the multilingual legal counseling service recently offered at the Brillat-Savarin High School in Berlin's Weissensee district. Other topics noted in the interviews: language difficulties, occasional bullying and racism within the workplace, problems changing jobs, and the housing situation: "Most trainees live in inhumane housing conditions: They cannot afford an apartment. They live (...) with several other people in a cramped and poorly equipped room without a rental contract and with high rent," the document states.

The vocational school in Berlin-Weißensee bears the name of a French soft cheese, Brillat-Savarin, which in turn is named after a pioneer of gastrosophy, the study of nutrition and food cultures. All those completing a dual vocational training program in the hotel and catering industry in Berlin study here. This includes 700 trainees recruited in Vietnam and smaller groups from India and Georgia.

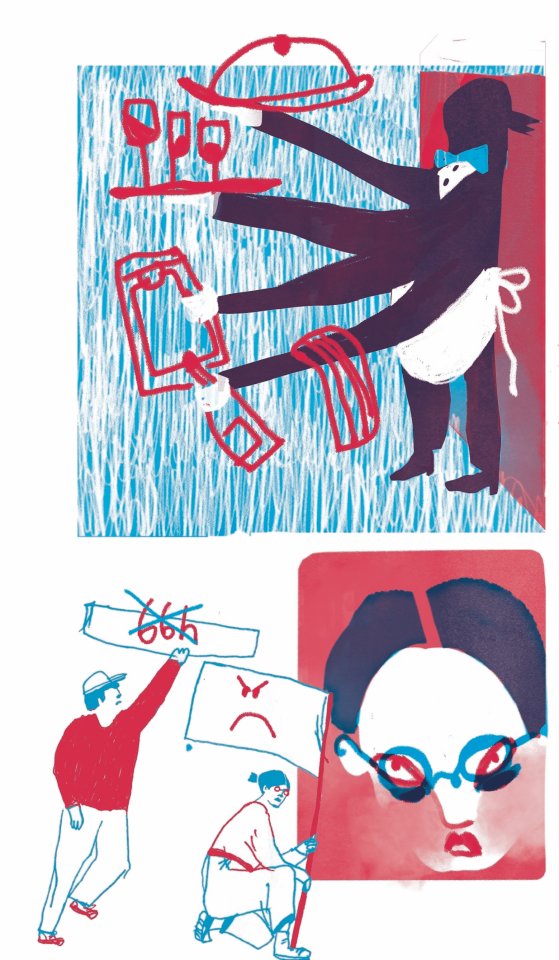

In mid-May, headmaster Jürgen Dietrich, along with teacher Ulrike Holaschke, sat on the Integration Committee of the Berlin House of Representatives and explained to the parliamentarians that for about three years, they had been "observing with great concern that young people, especially from Vietnam, are being deliberately sent to Germany by organized structures." His colleague spoke of "exploitation in companies, overtime, fear of employers, because, of course, job loss is often linked to it." The training conditions, according to Dietrich, were "sometimes very, very dramatic." The issue had arisen in the committee, among other things, after a Vietnamese trainee started a solitary protest in the fall of 2024 with a self-painted sign in front of the restaurant where he was often required to work 66 hours per week instead of the agreed 40.

The placement agencies are also a topic of discussion on several occasions. Dietrich says his students are "extremely dependent on the agencies, which is why they are afraid to open up to us." Holaschke emphasizes that the teachers are reaching their limits. "We would like your support," she says, opening her arms to the MPs.

On this day in the Integration Committee, it became clear: The recruitment system, as it is designed, puts trainees from third countries under pressure that is incomparable to the situation faced by German trainees. In cases like that of the protesting trainee who had to work 66 hours a week, the legal situation is clear: the maximum permitted working hours were far exceeded. Other cases, however, are formally legal or fall into a legal gray area and must first be resolved in court, as the phenomenon is still relatively new.

The Magdeburg Labor Court issued a potentially groundbreaking ruling in March 2024. A Vietnamese restaurant management trainee recruited by a hotel had sued for the repayment of €1,000 that a large industry association responsible for placement had withheld from her in the event that she failed to complete her training or changed jobs. After a few months, the trainee actually did so. The court ruled that the "contractual penalty" was inadmissible: Although it had been agreed upon in a supplementary contract, the court considered it to be "inseparably linked" to the training contract and therefore applied the Vocational Training Act, which prohibits such penalties, to the supplementary contract. The industry association was required to repay the withheld money to the trainee.

ILO Convention 181The fact that such questions have to be resolved in court at all and are not automatically prohibited is also due to the fact that private employment agencies are poorly regulated in Germany. However, there is a means of enshrining standards in law: ILO Convention 181 from 1997. It is intended to protect workers – including trainees – from abuse, exploitation, and discrimination, for example through licensing and registration mechanisms for private employment agencies. Furthermore, it stipulates that any costs incurred are never borne by the placed workers themselves, but exclusively by the companies seeking them (the "employer pays principle"), and prohibits clauses that bind workers or trainees to the company under threat of financial demands. However, the Federal Republic of Germany has never ratified Convention 181.

And apparently, it doesn't intend to. The Federal Ministry of Labor has declared that the convention will not be ratified because it would counteract the deregulation of job placement in Germany that took place in 2002. At the same time, the ministry sees it, "the provisions of German law are largely consistent with the objectives and regulations of the aforementioned ILO Convention, without the need for ratification." This apparently means that pure placement fees may not be charged in Germany. However, the ministry also admits that in practice these are often paid in the home country. Furthermore, agencies or training companies based in Germany often pass on "recruitment costs" that are not explicitly referred to as "placement fees" to the trainees. This means that the "employer pays principle" cannot be considered. The BMAS has said nothing about this.

In the absence of appropriate legal standards, some institutions in Germany that provide information on the recruitment of apprentices recommend voluntary measures. The "Companies Integrate Refugees" network, for example, which brings together more than 4,000 companies and has also been involved in the topic of apprentice recruitment for some time, has developed a checklist for "Cooperation with Placement Agencies." It advises employers to pay attention to criteria when using private placement agencies that are based on ILO Convention 181. However, everything is voluntary; these are merely recommendations.

Another institution that contributed to the aforementioned checklist, one that many recruited trainees encounter in their home country, was the Goethe-Institut. The German Cultural Institute is one of the institutions authorized to issue German language certificates upon passing the exam. These, in turn, are a prerequisite for a training visa. Binding standards for employment agencies in Germany would be desirable, says Nina Hoferichter, a consultant for migration and skilled worker immigration at the Goethe-Institut. And she wonders whether the new government will take up the issue. At least the coalition agreement contains this sentence: "We want to protect workers' rights within the framework of labor migration and consistently combat abuse."

Hoferichter also explains that she and her colleagues have observed the phenomenon of increased trainee recruitment since the early 2020s—back then, in 2020, the Skilled Immigration Act came into force. Since then, Hoferichter says, there has been a "shift"—legal access to the German labor market is now more frequently achieved through migration into vocational training. The rising number of trainees recruited confirms this impression. Even people who have already obtained a qualifying degree in their home country are increasingly taking the vocational training route.

Doing it yourself is betterThis was also the case for Omar Brahimi (last name changed), who came to Thuringia from Morocco and now lives in Frankfurt am Main. The 29-year-old successfully applied for a program run by the German Society for Economic Cooperation (GIZ) in 2020. He had already completed an apprenticeship as an electrician in Morocco. After being accepted, the COVID pandemic intervened, and the program was put on hold. Brahimi then took charge of the rest of the process on his own, obtained all the necessary paperwork, completed his language course, and applied to an electrical engineering company in eastern Thuringia. He had to get used to life in the small town. "The people there weren't very welcoming," he recalls. He also noticed that the company was trying to exploit its foreign trainees. He began to refuse instructions that seemed unlawful to him, such as when the company sent him alone to a construction site or on an assembly job abroad without counting the long commute as working time.

During this time, Brahimi also contacted the "Fair Integration" advisory project in Erfurt, one of the few support services aimed at recruited trainees. A striking difference: Anyone who googles online for foreign trainees will find placement agencies, but also numerous advisory websites and contact points for companies: health insurance companies, industry associations, the federal government – all of them want to help companies with recruitment. However, if trainees, thousands of kilometers away from home, need advice and help on their own, they have to search for a long time or already know about projects like "Fair Integration" and Thanh Dam's advisory center in Berlin.

In any case, Brahimi made an effort to have his previous training recognized and was able to complete it after two years. The company didn't hire him, he suspects because he didn't put up with everything. He now works for a large international company in Frankfurt am Main. He benefited from the fact that he organized a lot of things himself and had no intermediary who could put additional pressure on him: no dependency due to high debts to a placement agency or special clauses that tied him to the company.

Vu has had less luck so far. She was transferred to a branch of the hotel chain in Brandenburg. The situation there is similar to that at the previous location: just under ten employees and seven trainees from abroad. She lives where she works again, and superiors in the new hotel also threaten the trainees, she says. The placement agency to which she gave a lot of money has not been in contact since her arrival. But Vu is unwilling to accept the situation. With Thanh Dam's help, she is looking for a new training position. Omar Brahimi and Thuy Tien Vu share the experience that German authorities are not much help in this process, and that she has to seek support on her own.

This research was made possible by a scholarship from the Otto Brenner Foundation.

nd-aktuell