Poland's fertility rate fell to new low in 2024

Poland's fertility rate, already one of the lowest anywhere in the world, fell to a new record low in 2024, raising further concerns about Poland's demographic future with its shrinking and aging society .

In a new publication of demographic data for 2024, Statistics Poland (GUS), a state agency, revealed that the fertility rate – meaning the average number of children that are born to a woman over her lifetime – fell to 1.099.

GUS1,099 – TFR fertility rate in 2024 ⚠️⚠️⚠️ pic.twitter.com/QZpgte6XCg

— Rafal Mundry (@RafalMundry) May 30, 2025

That is just over half the figure that Poland recorded in 1990 (1.991) and well below the so-called “replacement rate” – the figure needed to ensure that the population does not decline – which is generally defined as 2.1.

While different agencies use slightly different methodologies to calculate fertility rate, according to the Population Reference Bureau, a US-based NGO, only eight countries in the world had a lower number than Poland's figure of 1.1 in 2024.

They include Singapore, Thailand, Ukraine (all 1.0) and, in last place, South Korea (0.7). Poland's rate is lower than Japan's (1.2), a country that has long struggled with demographic issues, as well as those of western European states such as Germany, the UK (both 1.4) and France (1.6).

Last year saw the number of births in Poland fall to a new postwar low of 252,000 while the number of deaths stood at 409,000, according to preliminary GUS figures. That marked the 12th consecutive year in which more people died than were born in Poland.

“The population situation in Poland remains difficult,” wrote the Central Statistical Office when releasing the figures. It added that “no significant changes should be expected in the near future” to ameliorate the situation given that three decades of low fertility rates means there are now fewer women of reproductive age.

The agency also notes that women are having children much later than in the past: in 2024, the average age of a woman when having her first child was 29.1 years, compared to 22.7 years in 1990.

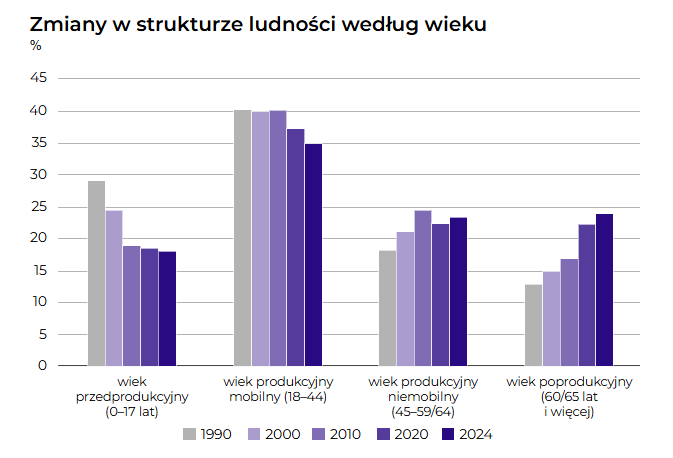

The Central Statistical Office also pointed to the “increasingly rapid aging of society”: in 2024, 23.8% of the population were above retirement age (60 for women, 65 for men), up from 16.8% in 2010, 14.8% in 2000 and 12.8% in 1990.

Changes in the structure of Poland's population according to age group, from the youngest (0-17) on the left to the oldest (above retirement age of 60 for women and 65 for men) on the right. Source: Central Statistical Office .

Speaking to broadcaster TVN about the data earlier this year, Agnieszka Chłoń-Domińczak, director of the Institute of Statistics and Demography at the Warsaw School of Economics, said that it is hard to pinpoint specific factors behind the falling birth rate.

“But the decline in the number of births could have been caused by factors such as COVID-19 and the subsequent war in Ukraine, which aroused uncertainty among young people, leading to a decline in the fertility rate,” she said.

While it will be impossible to reverse the trend in the coming years, Chłoń-Domińczak recommended policies to give young people more economic stability – in particular steady jobs and housing – in order to slow down the decline.

The scholar also pointed to academic research and opinion polls showing that the tightening of the abortion law in 2021- which outlawed terminations in cases where birth defects are diagnosed – has discouraged people from having children.

A recent University of Warsaw study found that, among members of Gen Z (born 1995 to 2012) the most commonly cited reasons for not wanting children were poor housing conditions, unstable work, and a difficult financial situation. But over half said that nothing would convince them to have a child.

Over half of Poles believe the near-total abortion ban, which bars terminations even if a fatal birth defect is diagnosed, has made people less likely to have children.

A large majority want to liberalize the abortion law but views are becoming more polarized https://t.co/UtdcxSu7Fy

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) October 18, 2022

Poland's previous government, led by the national-conservative Law and Justice (PiS) party, introduced a number of “pro-family” policies intended to boost the birth rate, most notably the “500+” (now “800+”) child benefit policy that gave parents a monthly payment for each of their children.

However, although there was a brief rise in the number of births after the introduction of 500+, the previous downward trend subsequently resumed, leading the PiS government to admit in 2020 that the policy had not succeeded in its aim of boosting fertility.

The current government, which came to power in December 2023, has maintained the benefits introduced by its predecessors and has also introduced new measures intended to make it easier for the parents of young children to return to work. It has also sought to increase the number of preschools.

Some of Poland's demographic deficit has been offset in recent years by levels of immigration that are the highest in the country's history and also among the highest anywhere in the European Union .

The number of foreigners in Poland's social insurance system rose 6% in 2023 to reach 1.13 million. Immigrants now make up almost 7% of all those in the system

The largest increases were recorded by Belarusians, Ukrainians, Indians, Colombians and Nepalis https://t.co/eA1QVo0ydH

— Notes from Poland 🇵🇱 (@notesfrompoland) January 27, 2024

Main image credit: Kornelia Glowacka-Wolf / Agencja Gazeta

notesfrompoland