Sport as self-assertion | GDR contract workers: Out of the gloom

Ibraimo Alberto landed at Schönefeld Airport in 1981 full of hope. He wanted to leave his homeland of Mozambique behind, a country scarred by civil war and inequality. Alberto wanted to build a new life for himself in East Germany. Perhaps by studying sports science, perhaps with an office job. At least, that's what he had been promised.

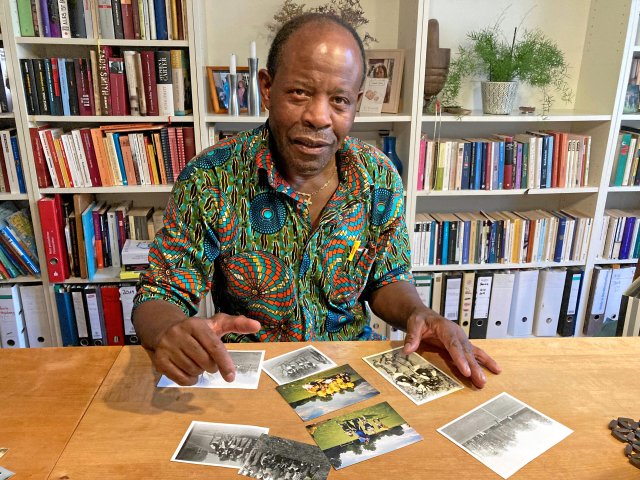

But Ibraimo Alberto is assigned as a contract worker to a "state-owned enterprise," a meat processing plant. He has to transport dead animals in long, monotonous shifts. He shares cramped accommodation with his colleagues. What distracts him? "From the very beginning, we played football," says Alberto. "That was our highlight."

The history of racism in sports is usually told from a West German perspective. In East Germany, the ailing economy relied on more than 90,000 contract workers. They came from Mozambique, Angola, and Vietnam. Daily life was marked by isolation and racism. What offered a distraction? Sports.

Training matches against club teamsIbraimo Alberto was not yet 20 years old when he arrived in East Berlin. He wanted to join a local club, but African contract workers were not welcome there. They were expected to work and then eventually fly home.

In Mozambique, in southern Africa, Alberto had organized football matches himself. He continued this tradition in East Germany . He approached other workers. They met for training and founded their own football league. He approached factories and savings banks for financial support. "We then had T-shirts made. The team from our meat processing plant was even mentioned in the newspaper."

Word of Ibraimo Alberto's dedication spread. With a selection of Mozambican workers, he played training matches against club teams from East Germany. They traveled to Leipzig, Dresden, and Wismar. "Many people underestimated us," says Alberto. "But we had a good team. Some of us had played in the first division in Mozambique."

State security checks in the dormitoriesGames like these were highlights for the contract workers. In their daily lives, they often had to perform tasks that endangered their health. They had to surrender their passports and hand over a portion of their wages to their home governments. "They were only taught as much German as was absolutely necessary," says historian Patrice Poutrus, who researches the topic. "There was no intention of them forming anything like partnerships with Germans." In some cases, pregnant contract workers were even pressured to have abortions.

In East German propaganda, contract work was portrayed as solidarity with the "brother states." In reality, however, inspections in the dormitories and the Stasi were intended to hinder close contact between contract workers and East German citizens. Ibraimo Alberto followed the rules because he didn't want to return to war-torn Mozambique. "If someone caused too much trouble, they sent them back," he says. "Then they were immediately drafted into the army in Mozambique."

The largest foreign group in East Germany, numbering 60,000 workers, came from Vietnam . Hoang Van Thanh, for example, arrived in Leipzig in 1988 and was assigned to a metal factory. He says he wasn't offered integration or language courses: "We wanted to build a new life for ourselves in East Germany. We didn't want to be dependent on anyone. So we kept a low profile. The Vietnamese community gave us strength."

This community was also interested in football. Gradually, Vietnamese workers between the Baltic Sea and the Ore Mountains founded 16 teams. They weren't welcome in the GDR's official league system, so they organized their own tournaments. Hoang Van Thanh, then in his early twenties, took care of pitches, jerseys, and coaches. The Vietnamese embassy disseminated the information in its newsletter. "Our daily life wasn't easy," Hoang Van Thanh recalls. "But football allowed us to experience our community."

Racism and deportation pressure after reunificationAfter the fall of the Berlin Wall, tens of thousands of contract workers lost their jobs and accommodations. Many returned to their countries of origin. The Vietnamese government resisted this and continued to hope for remittances from Germany. 20,000 Vietnamese remained in West Germany. Many became victims of attacks and racism, for example in August 1992 in Rostock-Lichtenhagen, when several hundred people, including many right-wing extremists, attacked a hostel for asylum seekers for days – to the applause of onlookers.

In addition, the former contract workers lived for years under the pressure of deportation, says researcher Patrice Poutrus, who grew up in East Berlin: "They also had to rebuild their lives like all East Germans. And at the same time, they had to ask themselves whether their fellow East Germans might also be their racist enemies."

Today the second generation is playing footballLong-time footballer Hoang Van Thanh also stayed in Leipzig after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He built up a textile company and continued to organize tournaments for the German-Vietnamese community, right up to the present day. He now receives support from the children of the former contract workers, including Bao Linh Huynh. "The second generation grew up in Germany," says the Dresden resident. "But through football, we can create a connection to Vietnamese culture and language."

Ibraimo Alberto, who grew up in Mozambique, holds a similar view. He was also a successful boxer in the 1990s. He trained as a social worker in Schwedt, Brandenburg. For several years he lived in Karlsruhe. But now, at 62, he is back in Berlin. Alberto worked with refugees for many years. He told them his own story, about his arrival and the racism he experienced. But also about his self-assertion, in which sport played a significant role.

nd-aktuell