Question of the day: should we demand bomb shelters from the authorities when they don't exist and won't?

For the fourth year running, the same situation has been repeating itself in Russia: whenever enemy drones reach another city, conflict erupts between residents and authorities. Activists demand space in bomb shelters, while local officials make every effort to deny the request and offer vague promises. Who is right?

This week the topic of bomb shelters heated up once again.

Famous actor and Ksenia Sobchak's ex-husband, Maxim Vitorgan, shared on his Telegram channel that while walking in the city of Tuapse, he "received a message about the danger of a drone attack and urged people to seek shelter 'in windowless rooms.'" Maxim began looking for shelter, but found there was nowhere to hide. But it wasn't the lack of shelter that struck him deeply, but the reaction of the locals:

"I look around... No panic. Nothing has changed. The city lives its own life. So, like the town madman, I wandered the streets and pestered people: what do you do in situations like this? Where should I run and hide? And so on. People grinned and waved their hands: they send automated messages every day—to deflect responsibility, like, we warned you; there's nowhere to run; nothing will happen..."

The attack continued all night. The actor "looked out the window: a couple of windows in neighboring houses were lit up, of course... but no one was running. There was nowhere to run. We slept in the bathroom—a windowless room. The only one awake was the Russian Avos'. He was protecting us."

Vitorgan's message spread through local social media channels. In the discussions, Tuapse residents confirmed the lack of bomb shelters in their city, despite regular drone attacks. However, Maxim faced criticism, being called a "touchy, useless actor," and the lack of bomb shelters was attributed to the difficulty of constructing them "in the local mountainous conditions due to the complex geological structure."

Examples of comments left by readers of the "My Tuapse" group included: "Bomb shelters are useless; who would run out of their home at night to hide from shrapnel?", "We are Russians and we know no fear," and "Strong-spirited people live in Tuapse; let everyone know that."

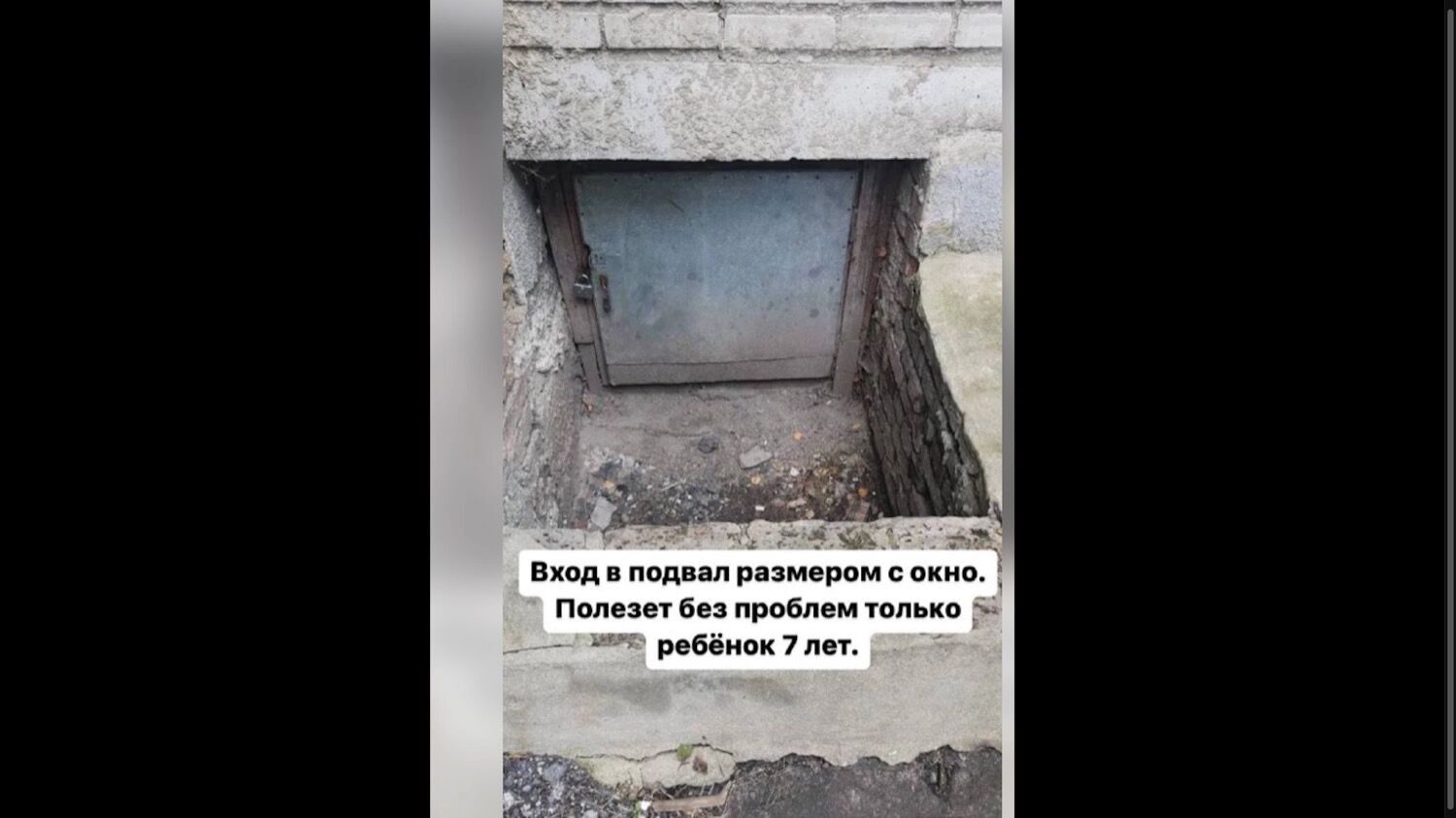

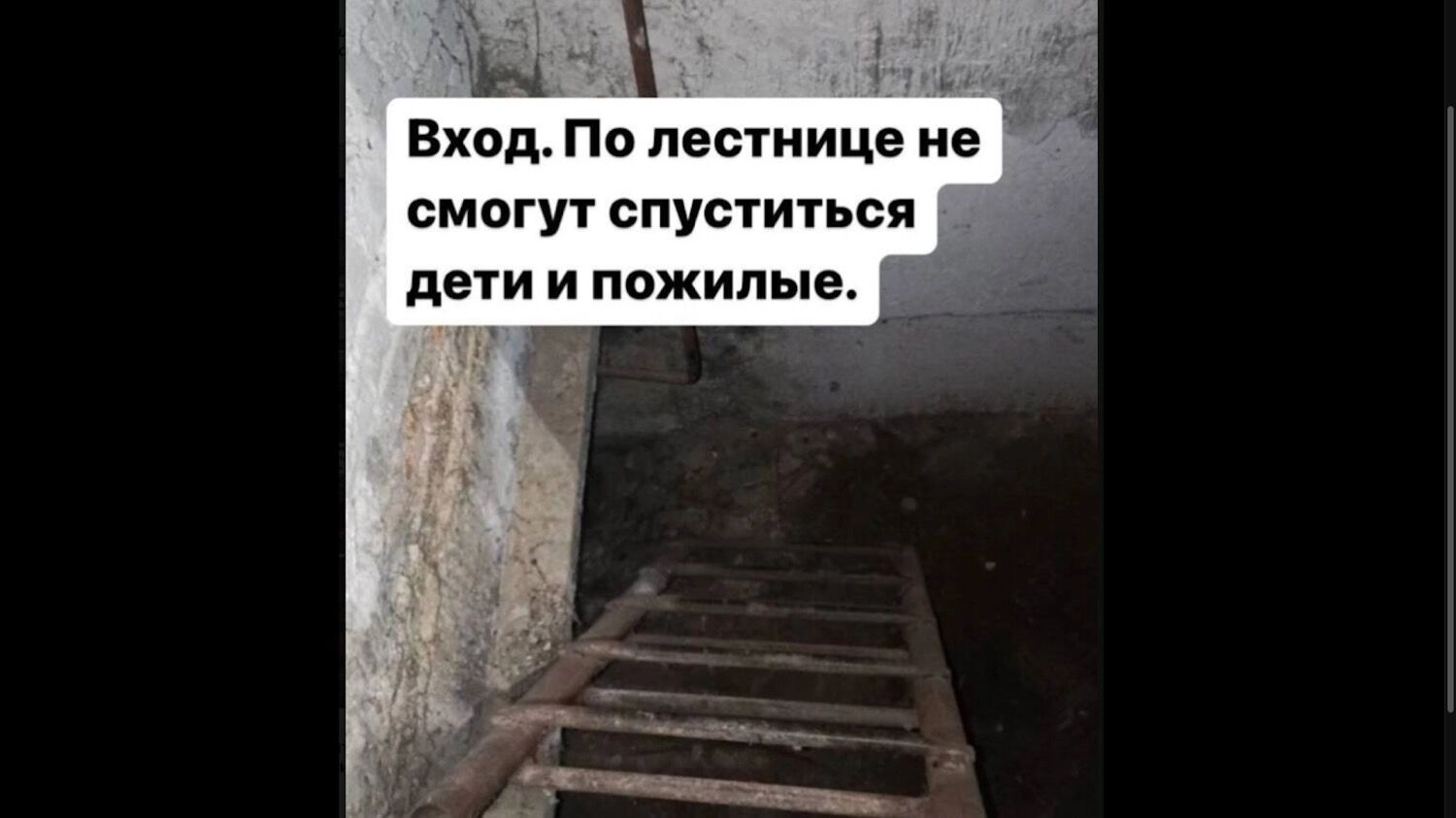

Not every residential basement can serve as shelter from drone attacks. Photo: Zarechny Residents' Public Page

But in Vladimir, there are residents and media outlets who are less resilient and continue to bombard the administration with demands for a list of shelters and cover in which to hide during enemy air strikes.

"Information about the number of shelters, their readiness, locations, and technical specifications is classified as 'for official use only,'" press service chief Yulia Zhiryakova responded.

According to city residents, most of the basements, designated as shelters during the Soviet era, were either flooded or leased and sold for storage, clubs, or other commercial purposes. Even though, back in October of last year, the mayor's office promised to conduct an inventory of the premises suitable for shelters and find the owners, the results of this work are unknown.

A similar situation exists in Ryazan, where drones from Ukraine regularly fly. One local activist raised the question of where to find safe shelter.

"The addresses of civil defense structures will be available on the State Services portal. Residents will be able to access this information soon," the mayor's office informed her , adding that "EMERCOM specialists are currently working on implementing the project."

A bomb shelter in Chongqing, China, has been transformed into a rainbow tunnel. Photo: China News Service/VCG/TASS

I immediately want to ask: what are the Ministry of Emergency Situations specialists working so hard on? Any high school student with computer literacy can map shelter addresses! On private websites in Ryazan, if you search for them in Yandex, you'll find such maps, created without the Ministry of Emergency Situations' involvement.

And it gets worse. The geography of the conflicts is expanding to the city of Zarechny in the Penza region. There, two years ago, proactive citizens organized a Public Control Committee and inspected the basements offered by the administration as bomb shelters.

"The situation is critical!" they declared on the social network VKontakte. "Access to some basements is extremely difficult due to narrow passages suitable only for children. In other cases, steep and cramped staircases make descent impossible for the elderly. There is no lighting, the floors are damp, and sand and piles of waste are everywhere."

During inspections, it was discovered that even management company employees didn't have keys to all the basements. In such situations, residents had to contact building managers to gain access. "In a critical situation, when every second counts, there simply won't be time for this," note residents of Zarechny.

According to estimates by the Public Control Committee, only about 20% of the allocated shelters are actually suitable for protecting the population. But the mayor's office and the Ministry of Emergency Situations are doing nothing to improve them. In desperation, residents of Zarechny even composed a song with the leitmotif, "Money laundered, pockets full, stalactites growing in our shelters."

Overall, it appears that the authorities are either inactive or assess threats to the civilian population somewhat differently than individual members of that population.

The second theory—that there are real risks to the population—is supported by the position of civil defense experts. The author spoke with one of them, a retired colonel with the Ministry of Emergency Situations, in an informal and off-the-record setting.

The officer immediately noted that he understood the emotions of people on social media who were experiencing drone strikes for the first time.

— Why are there not enough bomb shelters in our cities?

"Because a bomb shelter is a permanent underground structure with its own ventilation, radiation protection, communications, heating, water, and sewage systems, designed to withstand nuclear strikes or the bombing of cities with aerial bombs, missiles, or heavy artillery. Clearly, such structures weren't built everywhere in Russia over the past 50 years for one simple reason: the country is reliably protected by air and missile defenses. There was no point in burying billions in the ground. And even now, in the fourth year of the Second World War, enemy aircraft don't fly over our skies. They're afraid... Except, of course, in the border regions."

— But the drones buzz every night...

"You don't need bomb shelters to protect yourself from drones. It's enough to hide in a windowless room—a hallway, a bathroom, etc. And definitely don't run out onto the balconies with smartphones to film the explosion."

— Agree that a well-equipped basement in a house is better suited for this.

— Of course, yes. If the building has such a basement. I remember a couple of years ago in Lipetsk, they conducted a comprehensive inventory of three thousand apartment buildings. Only half were deemed conditionally suitable for temporary shelters—1,501 high-rise buildings, of which 500 were found to be only "limitedly suitable." Hundreds of buildings have no basements at all. They either have a technical crawlspace with a tangle of pipes and wires at chest height, or no crawlspace at all: the heating and water pipes run simply under the floors of the ground-floor apartments. But even if people were allowed in, what would happen if a hot water pipe burst? And how do you protect the building's utility systems—electric welding, communications, meters—from uninvited guests in normal times? We're told that access to shelters should be free at all times. But how does that fit in with anti-terrorism measures? What if someone wants to plant explosives?

There's another important factor working against shelters and hideouts: how can you lure people there en masse? It's no coincidence that the residents of Tuapse, accustomed to drones, responded bluntly to Vitorgan: "We don't run to any basements!" This is understandable: they're not even called there by public address systems.

"Try declaring an air raid alert for all of Moscow, a city of 12 million, at two in the morning, with the goal of forcing Muscovites and visitors to the capital from their bedrooms to take refuge in shelters and cover," the interlocutor suggested. "Can you imagine what would happen? And what will happen when it turns out the alert and mass panic were issued because of three to five drones successfully shot down by air defenses? So what about Moscow, which has hundreds of metro stations and hundreds of buildings with underground parking. But what about residents of Vladimir or Ryazan, where there's no metro, underground parking is rare, and only one in three buildings has a fully equipped basement, at best?"

Only 16% of protective structures in Russia are capable of sheltering civilians in the event of shelling or a nuclear explosion, according to a collection of materials from the 2024 Ministry of Emergency Situations scientific and practical conference. 17% of shelters and covert structures are only partially usable, and 67% are completely unusable.

newizv.ru